Everything or nothing. All of us or none.

Last week, I had the pleasure of reading Randy Ribay’s Patron Saints of Nothing, out next month. The book masterfully explore’s one young man’s attempts come to terms with identity, family, and death within the contexts of global post-coloniality and participatory culture. There are many, many parts of the book that I loved. However, the three word dedication is probably the moment I got really excited about the book:

As someone that’s felt like I’ve lived between and amongst a lot of hyphens, the dedication is one that spoke to me.

It’s a hell of a thing describing who you are. My multiraciality means splashing hyphens all over the page when I wade into positionality statements for academic research. It means having a name that autocorrects to anteroom. In my younger days, it meant feeling like I had to account to others for the fact that I don’t speak Spanish or Tagalog. I am so thrilled for these words to serve as an invocation for readers, writers, and learners who will get the opportunity to read this book soon.

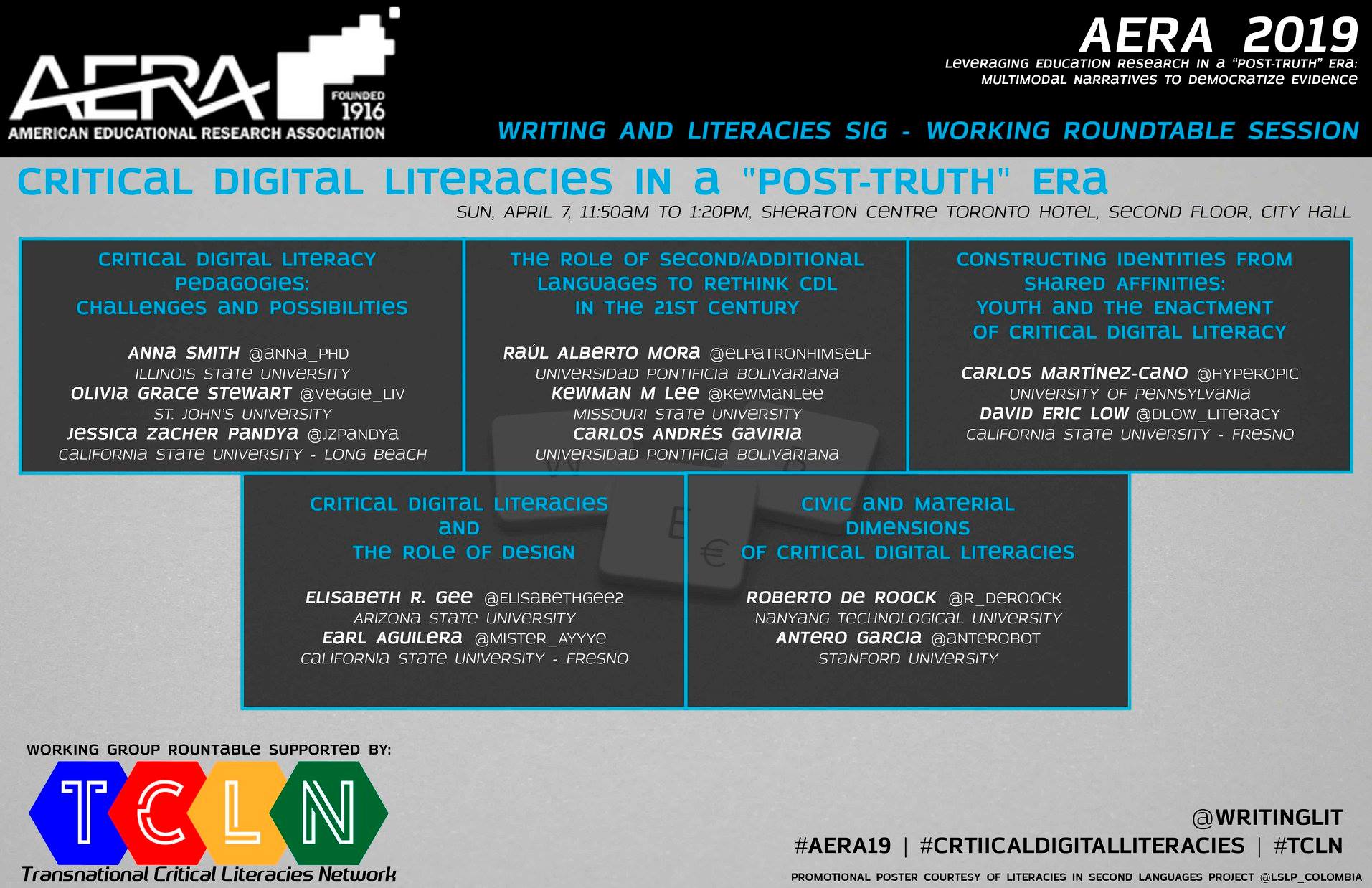

I’ve been ruminating on the beauty of those three, simple words from Ribay’s novel while also futzing with a scrap of notes I shared at a conference last year. The crux of what I was wondering about—in a ritzy conference center as my colleagues and I talked about educational equity whilst sampling crudités and cocktails– was the embodiment of a hyphenated present.

As educators, researchers, writers, and human beings that take seriously centering activism and love in the work that we do, it is past due for us to reconcile the hyphenated when we ask: What kind of future are we designing, co-constructing, co-authoring, co-dreaming?

This isn’t a question for laconic daydreaming. Rather, I’m reminded of how friend and mentor Kris Gutiérrez describes imagining as a transformative act of literacy in this article. It is in the moments of youth dreaming that the students Kris worked with became historical actors “who invoke the past in order to re-mediate it so that it becomes a resource for current and future action” (p. 154).

Hyphenated, historical actors act in every classroom today, as both teachers and learners. Ribay’s novel demonstrates that historical actors have the capacity to take historical actions.

A Reptilian Metaphor

As we explore and actively work within the hyphenated present, I want to propose a metaphor to frame the ingenuity of young people. In the film Jurassic Park (a movie staunchly influenced by second-wave feminism, don’t @ me), the following dialogue serves as a key introduction to the raptors that will terrorize our protagonists throughout the second and third acts of the film:

Muldoon : They show extreme intelligence, even problem-solving intelligence. Especially the big one. We bred eight originally, but when she came in she took over the pride and killed all but two of the others. That one… when she looks at you, you can see she’s working things out. That’s why we have to feed them like this. She had them all attacking the fences when the feeders came.

Dr. Ellie Sattler : But the fences are electrified though, right?

Muldoon : That’s right, but they never attack the same place twice. They were testing the fences for weaknesses, systematically. They remember.

(I’m getting this dialogue from the Jurassic Park IMDB page here)

I want us to be fence-testing the conditions of schooling, learning, and inequity, like patiently impatient raptors prodding for liberation. Fence-testing, as a means of speculating about alternatives to a mundane present, is an act that is engaged in collectively. Our fence-testing efforts can be interpreted as a means of exploring the boundaries and pathways for robust and sustainable diversity and representation writ large.

Like raptors clawing for a feminist revolution, we must engage in fence-testing as a means of distributed resilience that allows us to get free.

I started this post with a line from a Bertol Brecht poem. Often read as a clarion demand for labor movements and inclusivity, I can imagine Brecht’s line interpreted differently today. That “us” is a hyphenated “us” is a hyphenated “you” is a hyphenated “me.” And you accept all of us, of you, of me. Or you accept none. “Everything or nothing” is a personal demand: see our fullness as hyphenated selves wobbling in the crevices of the Anthropocene.

This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Challenge, a month-long movement to feature the voices of indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Kelly Wickham Hurst (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch up on the rest of the blog circle). You can read all of the blog posts this month here.