In case any readers are in the area, I’ll be speaking in the Graduate School of Education at Buffalo on Friday. My talk, “Analog Literacies and Digital Platforms: Hope, Fear, and Healing in a Climate of Rising Nationalism,” is part of the Dean’s Lecture Series. The talk is at 2:30 and location/info can be found here. Hope to see some of you there!

Why a Book on Comics Pedagogy?

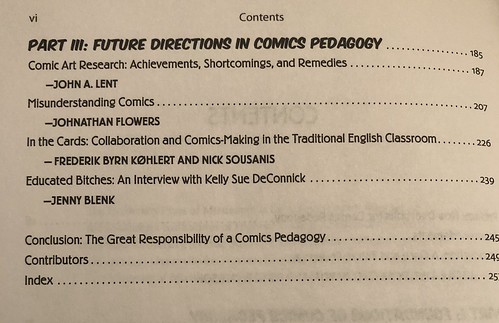

I am so thrilled to share the release of my most recent co-edited volume. With Great Power Comes Great Pedagogy: Teaching, Learning, and Comics is the kind of book that my two co-editors and I have been wanting to draw upon for quite a while. And so we worked—in collaboration with our contributors—to make this particular dialogue about comics and teaching happen.

Taking seriously a comics pedagogy, this volume brings together a pretty amazing list of folks from across very different kinds of contexts. However, what we intentionally wanted to do in this book was to put teachers (from K-12 settings to higher ed), comics studies researchers, and comic book creators in dialogue with one another. Some of these are literally conversations—like the interviews conducted with comic book luminaries like Kelly Sue DeConnick, Brian Michael Bendis, David Walker, and Lynda Barry. Some of these are discussions across the histories of comics studies. And some of these are analytical and empirical analyses of teaching with, through, and about comics in various schooling contexts.

While there is an abundance of interdisciplinary scholarship on the use of comics in learning settings, too often it feels like the knowledge shared in one corner of academia is too distant from the other dimensions of what I find makes comics—and the field of comic studies—so vibrant. We intentionally weave together various styles, approaches, and topics in this book to center the diversity of what comics pedagogy means and what is it for. The table of contents for this book is amazing.

And shout out to contributor, Ebony Flowers Kalir—her amazing artwork graces our cover. For real, if you haven’t read Hot Comb yet, get. on. that.

I guess if you’re not convinced, maybe the words of Henry Jenkins might help?:

(And there’s a review by Lee Skallerup Bessette recently published here.)

Finally, it this book was an honor to work on with my co-editors Susan Kirtley and Peter Carlson. Our editorship, too, is an intentional reflection of the interdisciplinary approach to this project. While I share a teaching history with Peter, he represents, here, the role of K-12 educators weighing in on comic pedagogy. Susan, is an Eisner Award-winning scholar and director of the comics studies program at Portland State University. And I approached this work indebted to the educational scholarship that has shaped my thinking about comics, literacies, criticality, and multimodality.

We’ll be hosting talks and workshops related to this book’s release at various comic cons throughout the year. Please consider checking out the book! We hope to get to geek out with you soon.

Dispatches for Luna & Max (#03)

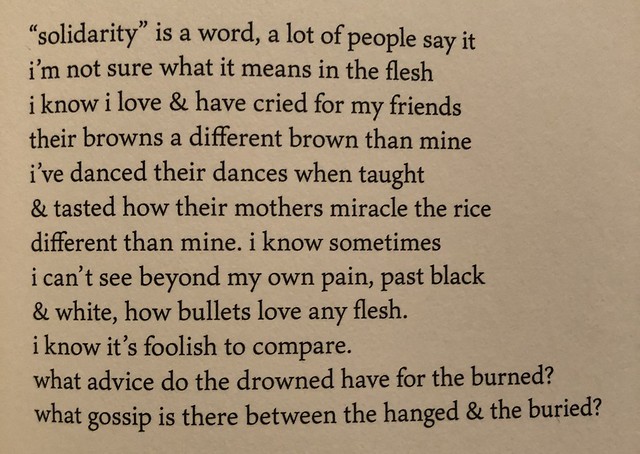

- From the poem “what was said at the bus stop” by Danez Smith.

- The poem is in their most recent book.

- The book’s cover says the book is called Homie and the book’s “note on the title” is one the most satisfying revelations I’ve encountered.

- I don’t think I sat as fully in the wondering of the word “solidarity” until this stanza and I think the links to history and to lineage and to empathy have had me on tilt in the weeks since I first read it.

- I couldn’t choose an excerpt from the book’s opening poem, “my president.” That poem–like the entire collection–sings and swings from one line to the next, unrelenting and unremorseful (just moresful?).

SoCal Folks! – UC Irvine Presentation – Friday, February 21, 2020

A quick note:

I am presenting findings from my tabletop roleplaying ethnographic work as part of the UCI Informatics Seminar Series this Friday. I am using this as an excuse to finally finish the fourth paper related to this fieldwork.

The talk is open to the public and I’ll be loafing around campus if anyone wants to grab a coffee. Information here.

Dispatches for Luna & Max (#02)

- The vamping/harmonizing warm-up for the first 20 seconds.

- The finger point to the recording when the piano comes in at 0:21, like she’s Timbaland introducing the world to Dirt Off Your Shoulders.

- The anticipatory breath at 1:06 before jumping into the song.

- When the make-up artist tries to join along by dancing at 1:38.

- Would I have watched this video as many times as I have if this song/version was ever properly recorded or released?

- Weirdly, defunct SoCal punk band Abe Vigoda did the closest spiritual cover of the song.

Dispatches for Luna & Max (#01)

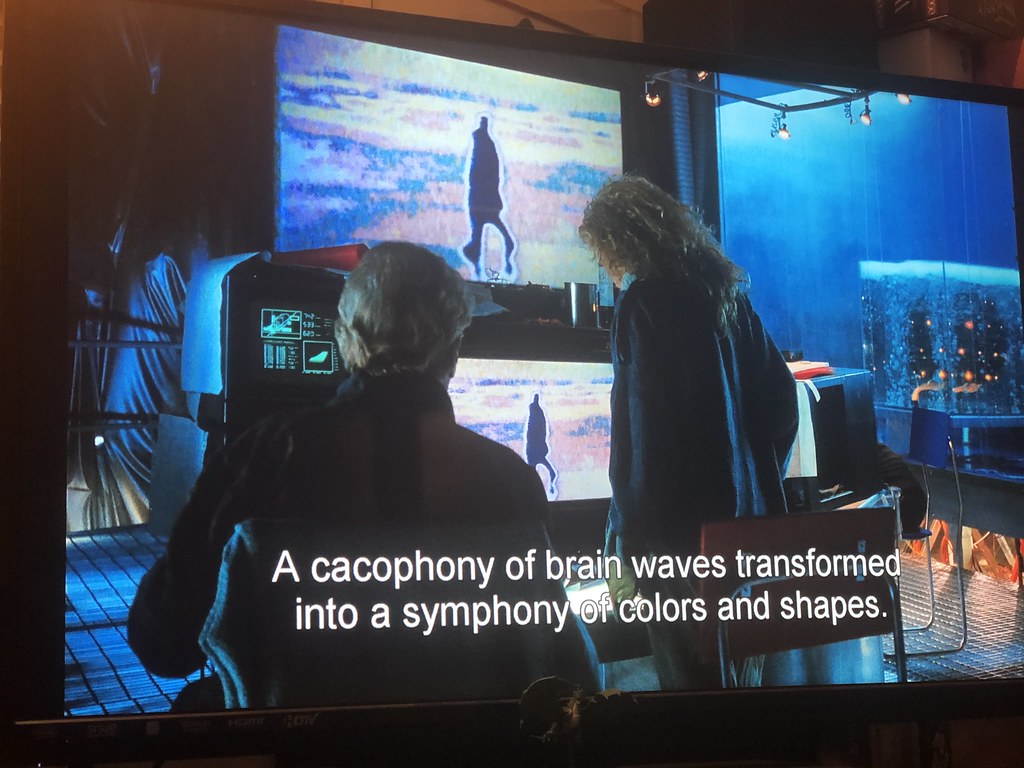

(from Until the End of the World)

To get back to posting around here somewhat regularly, I’m planning to tag occasional media–sounds, snippets, images, gestures–to revisit when Luna and Max get (a little) older. As an opening, this still from Wim Wenders’ film feels like an appropriate, meta reflection on memory, media, and meaning. If you’ve got a spare 4.5 hours, it’s a helluva film.

“We are ranking the great shipwrecks”: Books Read in 2019

Yesterday, I finished Jenny Slate’s Little Weirds and I’ve been slowly moseying my way through this collection of essays about Elizabeth Bishop. So here’s my breakdown of my reading for 2019:

Books read in 2019: 170

Comics and graphic novels included in reading total: 42

Books of poetry included in reading total: 8

Books reread included in reading total: 5

Academic & Education related books included in reading total: 15

YA and Junior Fiction books included in reading total: 26

Roleplaying Game-related books (rules, modules, settings – related to this research): 3 [I’m mainly writing up findings from this work now; unless something substantial changes next year, I’ll stop tracking these texts at this point.]

Some thoughts (as usual, here are my posts on books read in 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, and 2009):

Rather than bury the lede, I’ll share that Ally and I welcomed twins into our family in July. They are (usually) great! I’ll be referring to them by their middle names on this blog moving forward: Luna and Max.

Okay. So, the first half of the year was taken up with a lot of pregnancy-related books, most of which offered conflicting advice. (As parents might predict, the summer was filled with books related to baby sleep habits. These, too, largely offered competing and unhelpful advice; yes, I changed them and fed them and swaddled the hell out of them already.) The world of publishing around pregnancy and twins/multiples is much more limited and I found bits and pieces of these books useful in reducing some of the stress we felt in the first two trimesters; but I thought these were also pretty bad for the most part. (I may go more in depth on the pregnancy/parenting book genre in a longer post because I have #feelings about these texts, the market for literally the most mundane yet precious aspect of human culture, and the pedagogical expectations of mainstream books.) On the off chance that any readers are expecting twins in the near future (congrats!), feel free to get in touch–I’m happy to share some specific recommendations.

Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir, In the Dream House, was the best book I read this year. Intentionally unsettling, Machado pushes on the boundaries of form and genre while excavating trauma and abuse in a book that’s unlike anything else I’ve come across. It’s definitely a BSRAYDEKWTDWT-contender and, considering how much I liked Her Body and Other Parties, Machado is a new favorite writer.

And while I realize it got a ton of press, I would universally recommend Chanel Miller’s Know My Name. It’s not a pleasant read but I am grateful to have gotten to learn from Miller’s words.

Though eight doesn’t look like much in comparison to other kinds of books account for, I read a lot more poetry than in recent years. I’m going to shoot for one collection per month in 2020.To be honest, I was kicked back into a poetry mood as I ruminated on the loss of musician and poet David Berman earlier this year. Rereading his collection, Actual Air, was a painful reminder of Berman’s genius and humor, the title of this post comes from this collection. Likewise, I’ve been regularly coming back to Zadie Smith’s reading of Frank O’Hara’s “Animals.” The text has crept into a couple of my academic talks and part of it serves as an epigraph for a short essay coming out in 2020.

Nick Harkaway’s Gnomon was the weird, overly long sci-fi novel I had fun getting sucked into. It feels like only due to largesse did Ted Chiang release a new collection of stories this year. It is, of course, impeccable.

In terms of comics, Tom King’s Mister Miracle is a refreshing take on the superhero genre (and maybe a spiritual sequel to his Vision run). Not unlike In The Dream House, it’s a stunning mix of fitting within the confines of genre and form while also channeling pathos through every page. I also found the diary-style comics of Keiler Roberts to be exactly the sense of humor and reflection to take me through a sleep-deprived fall. Her most recent, Rat Time, is as good a place to start as any.

For a year and a half now, a couple colleagues and I have been systematically reading select YA books published across the past two decades. As a result, I read a lot of YA I didn’t like this year. I’ll note that—as frustrating and #problematic as I found the series—the Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants offers some interesting ideas around multimodal literacies. (Years too late to be any kind of warning, I’ll also note that the final book in the series is infuriating.) Also surprising, I found Sarah Dessen’s Just Listen was an intriguing book for thinking about trauma, romance, and multimodal composition. I guess you could probably say that about 70% of YA books, but how many of them feature a corded house phone, a parental car phone, and a cell phone all at the same time? It’s a pretty revelatory reflection of now-discarded social uses of technology from just a decade ago. As a recent book, Jason Reynolds’ novelization of Miles Morales: Spider-Man hit the comic’s tone perfectly while still hitting the same emotional and critical notes that I’ve come to consistently appreciate in Reynolds’ books.

In terms of music, I’ve been trying to play only female artists around the house to orient around dominant voices my kids hear singing as they grow up. We have a Luna and Max playlist that is bratty and whiny and loud. I try to cycle through that as much as I can. I’m thinking of collecting the scrapbook pieces of media—on that playlist or otherwise—and sharing sporadically on this blog in the future.

FKA twigs’ Magdalene was my favorite album of the year.

For being my least favorite album that they’ve put out, I really like Vampire Weekend’s Father of the Bride.

I did a lot of writing, in equal measure to Colleen Green’s album length cover of Blink 182’s Dude Ranch and to Sunn O)))’s Pyroclasts.

Synth-y, gloomy pop feels like the right vibe for 2019 in terms of national malaise. I’ve been listening to the new Black Marble album a bunch lately.

Lastly, six years ago I closed my year-end post noting that I’d been listening to this live version of Yo La Tengo’s song “Nowhere Near.” We use the album version as the song we play during Luna and Max’s bedtime routine, so—by sheer repetition—it’s the song I probably heard the most in 2019 and that’s great. Here’s the album version to help you put your year to rest.

Coffee Spoons 2019: What I Worked on This Year and Why

Like last year, I’m going to break down a bit of how my time at work was spent over the calendar year. The cycles of submitting, revising, (resubmitting,) and publishing do not at all fit within a traditional 12-month calendar. Google Scholar, for example, says that I published 8 articles over the past year. And while that’s true, the bulk of my time was spent working on material that will not see the light of day until next year (or later!). Rather than pushing in new directions, much of my work this year continues along the same pathways I described in last year’s post and the themes I note below should look familiar.

[I realize many of these links may not be accessible if you are not reading this from the hallowed proxy server of a university campus; if you are interested in reading any of the work below, please get in touch.]

Youth Civic Literacy Practices

As the primary theme across my work, I’ve been exploring youth civic literacy practices. Over the summer, Amber Levinson, Emma Gargroetzi, and I published our first set of findings from our analysis of the 2016 Letters to the Next President project. A couple of interviews about this work can be read here and here. We’ve spent significant time exploring this data set and I’m excited about the ways this study challenges existing assumptions about youth civic learning (and if you are a classroom teacher or know one, consider having your students participate in the Letters follow-up, Election 2020: Youth Media Challenge). In addition to this article, we expect to have several other articles related to Letters to the Next President trickle into the public in the coming months.

Nicole Mirra and I have also been exploring civic literacies in collaborative work for several years now. We’ve been slowly constructing a book-length argument about youth civic learning in the context of participatory culture, Trumpism, and high-stakes school evaluation. As one component of this argument, we published an analysis of the framing of civic learning within national policy documents like NAEP and the Common Core. More work in this area should be out next year.

Healing

Though I chipped away at the writing of this article over several years, my essay, “A Call for Healing Teachers: Loss, Ideological Unraveling, and the Healing Gap” was published earlier this year, continuing my focus on the need for teacher healing and challenging the assumptions of what counts as social and emotional learning. As I mentioned earlier, this was one of the most personal pieces of writing I’ve worked on. Along with a couple articles from last year, this work offers something of a conceptual framework on which I’ve been slowly working toward more empirical work around care, healing, and affect in classrooms. Some findings from these studies should be seeing the light of day by early next year.

Analog Play

I’ve continued to explore the learning and literacy practices around tabletop gaming. My article defining tabletop “gaming literacies” was published online earlier this year and is in the current issue of Reading Research Quarterly. Likewise, my co-authored article with Sean Duncan on the lives and deaths of Netrunner came out in Analog Game Studies.

Expansive Digital Literacies

Yes, alongside analog literacies, I am still very much exploring the role of technology and digital platforms. This past year, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Remi Kalir as we studied the literacy practices related to open web annotation. Our article in Journal of Literacy Research can be found here. Likewise, we had a summer-long open review process for our book-length manuscript for MIT Press’s Essential Knowledge Series. We are busily revising this book now (as in I shouldn’t even be blogging right now!) and I expect the book to come out sometime next year.

Playful, Equitable Learning Environments

All of the work I do is, ultimately, about trying to improve the learning experiences for young people and the ways teacher expertise is taken up more broadly. I’ve continued to spend substantial time thinking about project-based learning contexts for English classrooms with the Compose Our World project. Several articles (and a book?!) will likely see the light of day next year. Likewise, several of my advisees and I have been exploring the affordances of learning within the contexts of school busing. The equity dimensions of getting to school—particularly within the stratified contexts of the Silicon Valley—have been striking. We will be sharing some preliminary work from our study at the 2020 AERA conference, with the eye on submitting to journal in April or May.

I had the opportunity to revise and update my conversation with Henry Jenkins for his recently published book of interviews. Though the conversation is ostensibly about Good Reception, the interview probably offers a clear articulation of how all of the threads of play, technology, civics, and literacy I work on push toward equitable learning opportunities for students and teachers.

—

Again, that’s a recap of published “stuff.” As I said at the top, much of my time in 2019 was spent on work that I can accurately link to later. For example, by my count, between three and six books will be published next year that I either co-edited or co-wrote primarily in 2019. (Only one of those titles is currently available for pre-order, but it’s a good ‘un). Those took a lot of time. Likewise, data collection, study design, partnership development, IRB, and all of the other pieces of participating in the systems of academia take a lot of time.

Lastly, as I see a lot of end-of-the-decade recaps across the internet, I’m reminded that around this time a decade ago I was starting to think, in earnest, about the design of my dissertation. In that sense, the current summary of my work on Google Scholar—while inelegant in its presentation—is a near-accounting of my formal published scholarship across the decade. See you all for Coffee Spoons 2020.

An Annotation Annotation Invitation

Throughout the first half of the year, my friend and colleague Remi Kalir and I have been drafting a book about annotation for the MIT Essential Knowledge Series. In our view, annotation is one of those things that everybody does regularly but is ill-defined: it plays a central role in our interactions with each other and with technology, it is fundamental to various disciplinary and interdisciplinary fields, and i has remained a central human activity since long before print-culture of the 1600s. (Selfishly, my own interests in digital and civic literacies intersect with the writing and social practices at the heart of annotation and I wish a book about annotation broadly already existed before this one.)

Long story short, the entirety of our working manuscript is online and we are hoping you will participate in the slightly-meta process of annotating the Annotation draft. Using the PubPub open publishing platform, we encourage you to read, discuss, and review the claims we are making in this book. To be clear, this is not simply a navel-gazing activity. Alongside a set of blind-reviewers that will be providing feedback, Remi and I will be looking closely at the comments, critiques, and suggestions included in this annotation process in order to revise this book.

But here’s the thing: writing deadlines are a tricky thing! In order for us to finish our revisions in the fall, we are setting an official end date to this review period. This book will be taken offline for us to complete our revision on August 23. So if you want to offer feedback (or just get a sneak peek at the book before it hits the proverbial shelves in the future), you’ve got roughly two months to do so!

On Writing About Loss, Healing, and Supporting Teachers

I published an article in the most recent issue of Schools: Studies in Education. The full title is “A Call for Healing Teachers: Loss, Ideological Unraveling, and the Healing Gap.” I want to say a few words about how I wrote this article and why.

The first paragraph of the article is something of a content/trigger warning and something of a disclaimer: this article is about coping with grief as a teacher. It requires talking about pain and I try to acknowledge that 1. If that’s not the kind of thing you want to read about, don’t read this article for now (I get it) and 2. I share three different accounts of loss in the article but don’t presume that these are at all representative of others’ feelings of loss and coping.

With that explanation and warning re-stated, here are the first four paragraphs of the article:

Sometimes words are too loud for the sensitive task of sense-making they must endure. Considering this, the paragraphs that follow excavate and interrogate feelings of loss tied to my experiences as a teacher as well as those of my colleagues. I do not seek to essentialize these feelings but recognize that the process of defining and analyzing loss—the very project at the heart of this article—may feel unsettling. Staring back into the eyes of grief can be painful, confrontational, incomprehensible (Caruth 1996). I offer what follows as an analysis of loss, death, and uncertainty as intertwined with classroom teaching experiences. Furthermore, I want to be clear that grief ’s origins are myriad and it molds to innumerable shapes. I do not paint a definitive portrait of how it manifests in the lives of teachers. Instead, I seek to explore how the complexities of race, class, and gender within classrooms offer opportunities for teacher solidarity in healing, particularly within historically marginalized school communities.

My father died two months into my second year as a teacher.

Perhaps the one saving grace of teaching on an otherwise inequitable year-round schedule was that I had ample time to spend with my father in his remaining weeks in a hospital. With the months of September and October of that year set aside as a break in our academic year, I had time to mourn before returning to the needs of the eleventh- and twelfth-graders in my classroom.

I swam through the first half of that school year numb and confused. Flashbacks of the beeping IV jellyfish that accompanied my father in his final weeks and his strangled raspy breaths in his final hours would invade my attempts at teaching American literature and half-hearted bouts of grading papers. I wasn’t prepared for the tangled feelings of personal grief and professional responsibility that I faced daily that year. From all outward appearances, I taught and acted like I did the previous year. I also often felt similar: confused, lost, overwhelmed. I wasn’t able to separate my sense of being overwhelmed by work from my feelings of being overcome with grief, and so I went through the year assuming that this was how most teachers new to the profession felt. Scholarship from my teacher education courses, discussions with veteran teachers, and conversations with friends who were also wading through the debris of neophyte teaching converged around the steep learning curve of the profession. For better or worse, the creation myth of teacher preparation dictates that this is what becoming a teacher feels like: a phoenix-like transformation, a soul-crushing process of exhaustion, confusion, and embarrassing missteps in the classroom that, a few years on the other side, would produce a world-weary teacher ready to battle the great day, year, and career of teaching.

I wrote this article amidst growing frustration with the lack of emotional support for teachers, particularly in the context of escalating violence and politicized fear. I wrote this prior to my co-authored essay focused on healing in an era of Trumpism. That it’s published now—amidst constant headlines of school-related gun violence and of legislation that restricts the rights of women over their own bodies and of the myriad other forces that are causing trauma and pain to teachers daily—feels fitting.

I’ve continued to grow frustrated with the limitations of social and emotional learning (SEL) as a means of supporting teacher life. And so, while I offer a few ideas of how to move our field of teacher education forward, I wrote this article committed to trying to push for healthier ways to support teachers in classrooms today. If you are a teacher or in teacher ed and doing this work around healing as well, I’d love to continue a dialogue with you (I am not presuming this article is by any means the start of this conversation… we’ve been circling these topics across happy hours, across hashtags, and across strained text messages and phone calls for a long time).

As a final note, I know that the acknowledgments sections of articles are usually skipped over. They are typically a place for nodding toward funders and reviewers. But I do want to pull some attention to words often overlooked and placed so near the gutter:

I would like to thank Victoria Theisen-Homer and Lauren Yoshizawa for their substantive feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I also want to thank the two anonymous teachers who allowed me to share their stories in this article. Finally, I want to recognize the powerful contributions of Antonio N. Martinez, whose contributions as a scholar and as a friend weighed heavily on me as I completed this article.

A lot of help goes into the academic labor of publishing. I benefit from the often overlooked labor of thoughtful respondents. I get to share the words and experiences of two anonymous (and amazing) teachers that allowed me to learn alongside their narratives. And I wrote this article sitting in the powerful scholarship of a friend I wish I could still continue to learn with and from. While there are a lot of “I”s in this article, it was built from the generosity of time, of ideas, and of friendship of a whole lot of other folks.