Last month, Remi and I had a conversation about annotation, graffiti, and school equity for the iAnnotate conference. We build off of the ideas in our book and the ongoing #AnnoConvo. If you’ve got 55 minutes to kill, here’s that video:

Category Archives: Technology

Make Your Own Gathering: Lessons Learned from Co-Organizing the #SpeculativeEd Colloquium

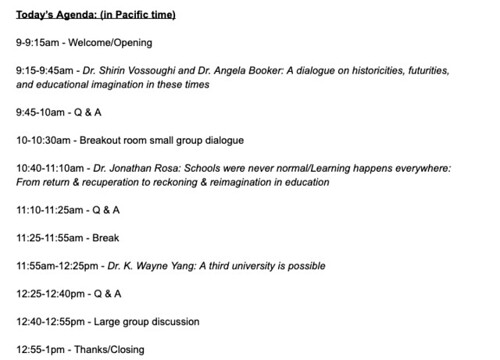

The Speculative Education Colloquium took place last week. Across two days of breakouts, featured speakers, and engaged online dialogue we expected a couple dozen people to join us for this event. We had several hundred sign up instead. In terms of our original hope of furthering a space for imagining critical pathways forward in education and educational research, the event feels like a successful one, though there are some areas we learned from that I think we can share with others here.

Y’all, I’m losing my mind. So excited to learn with all of you. #SpeculativeEd pic.twitter.com/M3F0BlFupb

— Antero Garcia (@anterobot) April 21, 2020

While the substance of the convening will hopefully yield breakout groups, offshoot gatherings, and classroom practices that may funnel into the public in the future, I wanted to reflect on the process of putting this event together and some of the lessons that Nicole and I learned. We announced the event three weeks before it took place and–including selecting dates, format, and inviting speakers–the entire project was a month long from start to finish. This design post-mortem is intended to help others plan for similarly-scaled events utilizing online virtual platforms.

Make it Happen

The biggest piece of advice that I think we can convey is that–if you are at all interested in bringing folks together, to sustain community and to engage in collective dreaming–do it. There are a lot of us sitting in physical distance from one another who are ready for something (virtually) tangible for us to work toward or learn from. To be honest, my own scholarship has suffered over the past two months. Stringing together academic writing, engaging in sustained data analysis, doing the hard work of substantial paper revisions: these are things that, cognitively and emotionally, I am having a hard time attending to right now. I imagine that’s the case for a lot of us. However, bursts of energy (ahem, maybe blog post-length): I can do that. And so, whether it’s hosting gatherings, writing shorter, accessible essays, or reviewing academic manuscripts, things that take discrete sets of time to complete are at least conveying the feeling of productivity (for myself) during a time when it’s okay for us to not actually be productive; this labor/market tension–particularly in the academy right now is a slippery one–I’ll probably ramble about this elsewhere. The convergence of this anxious energy with the willingness and creativity of an academic collaborator I’ve been lucky enough to learn alongside meant making space to create this event feel rejuvenating and personally useful. If any of this resonates with you and having a community to engage around your thing would be useful, do it. While somewhat labor intensive, this was a fun event that I feel nourished by. You can do this too.

Lower the Stakes and Under Promise

As mentioned above, Nicole and I (really) expected a handful of people to join us. We expected this to be a low-stakes event for sustained conversation for a couple days. For us, we had time open on our calendar because AERA was cancelled and–worst case scenario–the two of us would use the time to talk about a topic we were interested in. Even if no one else came, this event’s space and time would have been useful for us: it was a no-lose situation.

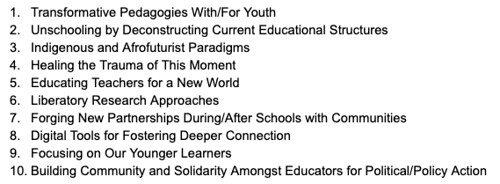

Once we sent out a general invitation to speakers and to the general public, we didn’t make any grand promises: come gather for a bit and we’ll see what happens. It’s free and so if you don’t like it or you can’t make it anymore, no harm done. We did ask participants what they were interested in (and saw a wide range of responses). That feedback shaped our breakout rooms and hopefully led to smaller, independent activities that could emerge from the event’s collaborative document.

Be Flexible

Once 100 people signed up for the event–two days after it was announced–we figured about half of those people would show up and the event was now larger than what we originally envisioned. We were in a tricky situation: we were too big for a collective dialogue (or at least we thought we were) and we were lucky enough to have all of our speakers confirm that they would participate. This made our schedule tighter than we expected–instead of having a few dozen people in close conversation with Megan Bang, for example, we could all listen to her, have limited time for Q&A, and have two breakout sessions. This wasn’t what we planned, but we went with it. If you are doing an event like this, consider how you might scale the context to accommodate larger and smaller groups. Further, how can you do this scaling in the moment? For example, we had a large number of breakout rooms prepared to be facilitated by friends; if we had much fewer attendees, we would just cancel a few of these rooms to make the others create fuller spaces (this didn’t quite work out and I’ll talk about that below).

Learning with and from Dr. Wayne Yang. I cannot communicate clearly how my shit is being dismantled… #SpeculativeEd pic.twitter.com/m0y04o1nRS

— Michelle King (@LrningInstigatr) April 22, 2020

A quick note on sign ups: before the event started just over 400 people signed up. We circulated this invitation only via tweets and Facebook posts and hoped it reached people who were interested via word of mouth. Of the people signed up, we had a peak of 220 (or so) people during the colloquium and the number dipped as it got closer to each day’s conclusion. We expected about half of the people signed up to join and that seems like a decent rule of thumb for online, free events in general.

Find Synergies

We knew most of our speakers would likely have attended AERA and so the ask for their participation was an easier one. This event intentionally moved alongside similar scholarly interests–our framing for the event was based on the invitation by Drs. Na’ilah Nasir and Megan Bang and clearly aligned with the scholarship of each of our speakers. Though these speakers were clearly making innovative leaps in the new work they presented, the request to share within the context of this colloquium wasn’t exactly out of left field. I do want to note that, as a free event that was not affiliated with either of our institutions, we did not have funding to compensate the donated labor and energy of our six speakers. That is something I think we would try to address differently in the future, if we were to do one of these events again.

Be Vigilant

The things that Nicole and I were most worried about were chat spamming, zoom-bombing, and other forms of online harassment that might have occurred. Two days before the event, the AERA online Presidential Presentation had to turn off chat functionality during Dr. Vanessa Siddle Walker’s powerful address because of comments made in the chat. Particularly considering that all of our speakers were presenting from and addressing scholarly and personal commitments to historically marginalized communities, making sure that online harassment did not occur was our fundamental concern and point of stress for the event. We know that the forms of harassment that we are concerned about disproportionately affect BIPOC, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.

To our knowledge, we did not have any issues with trolling or harassment during the event. While we cannot account for private messages that may have been exchanged or communication after the event, I feel proud of the work we did trying to ensure this space was a safe one.

We spent substantial time prior to the event testing out and confirming security functionality for the Zoom. We only sent links to the password-protected Zoom the night before the event, to minimize interlopers. We had a waiting room and let people into the event by first trying to confirm their names based on our sign up. We had multiple co-hosts of the Zoom and we were all in communication on a Slack channel identifying potential usernames we did not recognize or comments that raised any flags for us. We all had practiced the processes for turning off chat, ensuring participants could not share their screens, and–if need be–kicking people out of the event. When speakers were presenting, we also disabled participants’ ability to unmute themselves, ensuring the speakers would not be interrupted. These sound draconian, but we would rather a vigilant enforcement of safety than an unsafe space for our participants and speakers.

Most importantly, we wrote–and announced each day–a code of conduct for the colloquium. This was substantially adapted from a policy written by the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of the NCTE.

While I don’t love the need for such rigorous moderating of the event or the fact that so much of this insecurity is based on our over reliance on proprietary software that governs so much of our online interactions, it was the choice we made. We could have spent substantial time at the beginning of the event establishing collective norms with our participants–if we were a smaller group we probably would have. However, given that we wanted to prioritize the content of this colloquium, we went with the decisions noted above. I would be curious what strategies others are employing right now.

Ask for Patience

There are a lot of ways this event could go wrong. At the beginning of both days and in our email communication with participants, we asked everyone for patience as we collectively figured this out. Maybe it helped (?) that the first email I sent out about this was unintentionally formatted wonkily, immediately lowering people’s expectations (fortunately, Nicole took over emailing participants for the event moving forward!). Again, because this event was free, if things didn’t quite work out–like when the Zoom meeting abruptly ended for everyone at the end of Day 1–we could all smile and let the learning and convening continue.

Some Pain Points

There are a few areas we know we could have improved in this event and I share these below.

Access

We could have been better when it came to accessibility for this event. Yes, that’s the case broadly in schooling and particularly for forms of distance learning right now, but for our event, this could have been better. Three weeks prior to the event we started looking into captioning options. We made weekly progress getting the right APIs to talk with one another to enable automated captioning; while we didn’t have funding to hire someone to type captions for the event, we were planning to pay for the cheaper and still less ideal automated captions. Up to 24 hours before the event took place, we expected this to be functional. However, with various security levels to fiddle with Zoom, we were not able to get this option set up in time. We are aware that this likely affected some participants’ engagement. To be clear, this isn’t the only form of accessibility we needed to consider and this event had shortcomings among multiple lines in this regard. Early on, we acknowledged that a virtual convening like this one privileged folks with access to strong internet connections, for example.

Recording

This is less a pain point for us than for people who want the content from speakers. Even before the event was concluded, we were getting requests to share the videos of the speakers from the colloquium. Honestly, every speaker was amazing. And while we will share some of these talks very soon, we also were explicit with our underpromise in this regard. We only recorded the speakers’ presentations, cut off the recording once public Q&A began, and conveyed to everyone that we were uncertain if these recordings would be made available publicly. Again, our intention wasn’t to amass and collect others’ knowledge. After the colloquium, we emailed each speaker a link to download their own video recording. It is their work and their file to decide what to do with. We wanted to shift responsibility around this work to give back to speakers–particularly scholars that data suggests are often less cited or recognized for their contributions–to ensure that knowledge is both preserved and moved forward in ways that are responsive to individuals. Depending on your event, we could imagine you choose to record or not record in different ways, but think intentionally about what that recording light on Zoom calls does for participation. Speaking of …

Participation

We collected comments and questions from the chat, asked participants to “raise their hands” through Zoom’s functionality, and had a robust hashtag on Twitter as inputs for participation. There was also a powerful social annotation effort happening alongside the event. However, the size of the event meant that these structures did not ensure that everyone’s voices were heard. It also meant that it sometimes felt like there was a disconnect or lack of engagement from the large group if questions didn’t flow for speakers at some points. It also didn’t help that Stanford’s Zoom settings disable copying text or clicking on links.

Some strategies we used to mitigate these limitations—that might be helpful for you—included abundant use of customized tinyurls and an open google doc. The tinyurls were easy to share on a screen and, even when participants couldn’t click them, weren’t too difficult to type into a browser. In general, all of our information was distilled to a single, read-only google doc that we updated frequently. On this doc, we would post the agenda, links to all breakouts, links to related information, and things like a concluding evaluation form and the aforementioned google doc. In essence, if participants could access this document they could get to any other materials for the convening pretty easily.

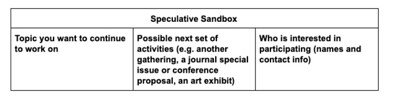

The open google doc functioned as a sign-in page so that participants could share contact information, converge around interests, and offer any relevant resources. There was a “sandbox” that we encouraged individuals to use to cluster around projects and topics–revisiting it now, there are several pages of potential projects that were born out of this event. This was an unorganized space and—again setting lowered expectations—we were not building a listserv or database to share later. Rather, we hoped people would use this space in the moment. At the beginning of the first day, we hit the limit of how many participants could be on this doc at any given time, so this may not be a feasible space for events of this size or larger.

Breakouts

Our breakouts were named based thematically on the interests people listed when they signed up for the colloquium. Participation in them varied widely. Some breakouts had 30-50 people in them and some had 2 people in them (though facilitators noted that these smaller groups had robust and personal conversation as a result). Because we didn’t want to sort people manually into groups or to assign people to random rooms, we solicited the help of friends that we knew signed up for the event. Since most of us have institutional Zoom accounts, Nicole organized rooms using multiple folks’ accounts:

Again, the read-only google doc served as the hub for finding these sessions. In addition to a host for each room that served as the space’s facilitator, Nicole also created a note-taking generic document. This page was shared with breakout rooms individually. All of these spaces, links, and organization took time in advance to make the day of the event flow somewhat seamlessly.

Returning back to the main meeting space from Zoom—like reconvening from group activities in a class or like a broader conference session—took time and we should have given ourselves more of it for this. We also saw some drop-off of attendees (who likely chose not to participate in the smaller breakouts); this didn’t surprise us, but I note it here for your own planning considerations.

Competing Activities

The same week that we announced this colloquium, Nicole and I also shared an adjacent (but different) idea, called #RogueAERA. Our attention to this colloquium meant we didn’t spend as much time on #RogueAERA, though there were some amazing contributions to the hashtag. However, because we had two different (but kinda related) hashtags floating around at the same time, we saw a lot of overlap between the uses of these spaces. Both #SpeculativeEd and #RogueAERA served as back-channeling spaces for the event, even if that wasn’t our intended outcome. I note this here to consider how you might make clear the boundaries of your space and the need to be flexible when participation begins to seep beyond those boundaries.

What’s Next

We aren’t sure! There are so many different things that could emerge from this colloquium. None of them have to be organized by Nicole or by me. This is an open invitation for others to lead the what’s next. I know this event is helping shape some of my own thinking and it is helping me ease back into the scholarly writing I had been adrift from.

Finally, about three weeks prior to the event, we did receive–via the Center to Support Excellence in Teaching–the support of Stanford doctoral student Kelly Boles; she played a substantial role organizing and working on the logistics with us. We really appreciate getting to learn with Kelly on this project. Alongside her, we are also grateful for the support of friends and colleagues that hosted breakout rooms, Joe Dillon and Remi Kalir’s work facilitating the social annotation for this project, and the many participants that tweeted or contributed resources throughout the event.

Free Access to Good Reception

Related to what I wrote on this post, my book, Good Reception: Teens, Teachers, and Mobile Media in a Los Angeles High School can be read (and I think downloaded) for free here for the foreseeable future.

The book is a part of a larger collection of titles that MIT Press has made accessible as a resource in response to COVID-19.

If you end up using this book as part of a teacher study group or in a course, please get in touch! I am happy to answer questions or join a discussion.

#rogueAERA: An Invitation

Many across the education research community are experiencing the cancellation of the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) through the lens of loss. This loss encompasses the hard work that President Siddle-Walker, Executive Director Levine, and so many staff members and volunteers committed to curating the program and organizing logistics, the efforts that thousands of educators made to prepare proposals and papers, and the ache that comes with losing an opportunity for in-person fellowship with dear friends and colleagues in a time of anxiety and uncertainty.

We feel the loss, too.

But what if we could simultaneously interpret this cancellation as an invitation?

Perhaps we could embrace this moment as an opportunity to expand the bounds of our community, re-imagine how we talk about education research, policy, and practice, and dream about the future of education together.

go rogue: to begin to behave in an independent or uncontrolled way that is not authorized, normal, or expected

– Merriam-Webster dictionary

What if we created a #rogueAERA?

Freed from the conventions of papers or posters or symposia, let’s consider how we could express the nature, goals, and findings of our work (and play) in education. Photos. Poetry. Songs. Tweets. Games. Illustrations. Videos. Stories. Dialogues. TikToks. And more. Go rogue.*

To be clear, we use the term ‘rogue’ in the spirit of embracing the experimental, not the negative or confrontational. We love our AERA community and while this effort is in no way affiliated with the organization, we humbly propose it as a friendly innovation.

Allowing ourselves to express what we do beyond the bounds of traditional academic forms can potentially create space for new innovations in our thinking and welcome more voices into conversation. Our families can participate in #rogueAERA. Our young people can participate in #rogueAERA. Let’s demystify it and throw open the doors.

And so, if you have the bandwidth right now (in every sense of the word), we invite you to experiment with us. During what would have been the dates of AERA 2020 (April 17-21), use the hashtag #rogueAERA on all social media platforms from wherever and whenever you are to share what you would have liked to talk about in person. Let’s start a new conversation.

–Nicole Mirra & Antero Garcia

*Disclaimer: We of course have to give the reminder that whatever you share on social media must respect the privacy of any research participants and cannot violate the protections upheld by institutional review boards and bonds of trust and respect. You know the drill.

Join Our (Online) NCTE Gathering

This Tuesday (and I *think* for Tuesdays for the foreseeable future), NCTE is hosting an online gathering for its members. It’s an evolving thing; its structure will match the needs of our members. I’m facilitating this first one and–if you are interested–you’ll need to RSVP at this link.

The format will be a Zoom call, the goal being to function as a disciplinary hub for English teachers to check-in with one another and share some social presence in this moment of physical distancing. I am honored that Dr. Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz has agreed to open this first gathering with some poetry from her recent collection.

It’s been hard to work in light of a world changing hour by hour around us. I am hoping these kinds of digital nodes can help ground us in each others’ presence as well as become touchstones for designing for the new. See you all soon.

Cancel all Classes Right Now: Kids are Scared, Teachers are Stressed, Our Country is Sick

Tonight I did a 10 p.m. run to the grocery store and the empty shelves here—and that so many friends are posting online—make it very clear: we are a nation in the midst of coping with a major crisis. This is a scary time and (finally) our government, major businesses, and public services are taking it seriously. Schools, too, are moving to online settings and to ensuring that students do not meet in physical spaces for the foreseeable future.

I get that teachers are scrambling to figure out the best ways to transition our work. I get that preservice teachers need a certain number of hours in order to receive state-based teaching licenses. I get that there has been a Herculean effort to get many students access to instructional materials in order to participate in virtual learning. But I also get that—both literally and metaphorically—our country is sick.

You don’t do school when you are sick. You heal.

When a school community is rocked by a natural disaster—an earthquake, a wildfire, a tornado–we don’t send students to Google classroom and we don’t ask teachers to prepare for distance education models. We heal.

By most estimates, a lot of people will get sick in the U.S. in the next few weeks. Many people will die due to complications from COVID-19 or perhaps from the lack of hospital-based care avaoilable for everyone. Businesses will close. Effects of this disease will be most heavily felt by vulnerable members our society; members of the gig economy that cannot take time off will suffer financially and in terms of their health. Depending on spread and our response, it is entirely possible that many of us will know people in our schools who lost family members as a result of this pandemic.

We can pretend to “do” school online for the coming weeks and months. We can force teachers to do this work in ways we have not adequately prepared them for. We can make students go through the rote exercises of pretending to engage in tasks that are not central to their current well-being. Or, we can call the charade off for a little while. Like we would in any other catastrophic scenario.

To be clear, I am not saying that students need to be sitting aimlessly as we weather this difficult time. I think informal learning that addresses students affectively is necessary. I think teachers need strategies to cope and to heal for themselves—including opportunities for reflection, for venting, and for reaching out to students as phone and zoom calls. I am also particularly grateful that districts made the difficult decisions to close schools while also ensuring plans for providing meals and other essential supports for kids right now.

While I am planning to do everything I can to help teachers who feel the double-bind of stress in new work settings and in a moment of peril, I am silently furious. A sense of mandated accountability undergirds the need for keeping students at pace in a world that is fully ruptured from any sense of normality right now. Look at the literal changes happening around us–this is not a normal situation and that, in and of itself, is important for students to see, process, and reflect upon as civic agents. As our country works to flatten curves and create social distance from one another, we continue to expect student academic performance to inch forward as if it is business as usual.

Three wishes for a virtual #AERA20

With AERA’s announcement that this year’s annual meeting is now a virtual one, there is a real opportunity for this conference to shift how thousands of educational researchers engage, interact, and view online learning opportunities. I have a sinking feeling we will collectively fail at this, based on every single other online conference I have participated in. They are terrible. Always.

At the same time, I spend a lot of time watching gamers and musicians perform live and interact with an audience. These are thriving communities and they are clearly getting it right. AERA probably needs to look closer to what a Twitch stream looks like for a charity event like Awesome Games Done Quick, for example (a bi-annual video game marathon that gets tens of thousands of viewers consistently during its weeklong duration).

Based on what I think will fail, here are my three hopes that I think would make this conference a successful one:

1. 1-Click participation

This is the thing I am most concerned about. If you’ve ever participated in an online conference, it usually requires registering for a system, downloading some proprietary software, and potentially waiting in a limbo-like screen until a session begins. It’s a confusing mess and nothing will turn off an audience faster than an experience that isn’t intuitive and seamless. It needs to be as simple as clicking a YouTube link and you are in. Literally that. Click, you are in. I am not necessarily a fan of YouTube as a platform, but if it means every AERA member can click a link and see a session at any given time (and it is later archived as an easily accessible YouTube video), I am all for it. More than any other aspect, this will be the thing that makes or breaks this conference.

1.a It’s not gonna be a regular conference

Okay, kind of cheating, but this is a continuation of my thoughts above. It’s no longer a face to face conference. That’s a given. So Do. Not. Try. To. Replicate. Traditional. Conference. Practices. For example, there is an intuitive chat feature on YouTube live videos – this would be an ideal space for a moderator to pull questions. However, I could imagine that a smaller group of viewers might want to actually talk after a particular presentation. Rather than resort to muddying an intuitive conference space for everyone, offer drop-in Zoom rooms (that can be recorded for later viewing if so interested) for further interaction and affinity-focused networking. For example, my amazing advisee is part of a 40-minute panel on the role of YA literature and equity in civic literacy contexts. The three panelists and discussant share slides to a live YouTube audience that gets 50-100 viewers (more than they’d probably get in a room at the SF-based conference!). At the end of the session, the presenter shares a link to a separate videoconferencing/Zoom room where they will be further discussing their research for the next 20 minutes. Maybe 6-7 other people join that conversation and the rest of the audience moves on to the next panel of presenters. It is a win-win: a more rewarding, smaller conversation, and an easily clickable YouTube link that works for all AERA members regardless of proxies, paywalls, or regions of the world. Let’s make this simple.

2. Ditch the names

With the exception of getting notable discussants and chairs to help contextualize new work, let’s use this space as an opportunity to highlight the voices that most benefit from being heard in these conferences. Doctoral students, post-docs, new faculty, practitioners—that’s who I would want to hear from. It should go without saying, but we need to specifically center Black, indigenous, and people of color in these presentations… but I probably need to say it anyways.

I am imagining each division and SIG is going to prune their program to a handful of sessions and I could see the inclination is to get the biggest names to ensure people tune in. They are not the people who need to be heard from. We need to put trust in the conference chairs for each section and the work they put forward, but I hope it isn’t just big name scholars. I can read their work already. I want sessions that challenge my thinking and introduce me to a new set of scholars I’ll be excited to meet in face-to-face contexts in the future.

3. Embrace Different Time Zones and Formats

The beauty of an organization like AERA is how many time zones our research spans. Since we are not confined to the whims of traditional working hours or hotel ballroom timeframes, why not shift to ensure that the conference is sharing work at all hours? It would be kind of amazing to get to click on a conference link at 3 a.m. in a given time zone and be whisked into somebody’s research from another part of the country (and if I am sleeping when the next great presentation occurs, it will be archived for me to catch up on anyway!). I’m writing this at 10:40ish p.m. on a Saturday as I watch my daughters sleep noisily on the baby monitor next to my desk. My working hours have not looked anything remotely like a normal 9-5 since becoming a professor and the 8 months of being a dad of twins has blown away any semblance of a regular schedule. I would love to feel engaged with a conference that lets me somehow plug in based on the time I have available.

Again, I think there is a real opportunity that comes with this necessary shift for this conference (and the many others that are being moved online for health and safety reasons). The more we put this conference behind log-ins and force it to adhere to traditional, physical conference rules, the more it will be an abysmal failure. Let’s not let that happen.

Coffee Spoons 2019: What I Worked on This Year and Why

Like last year, I’m going to break down a bit of how my time at work was spent over the calendar year. The cycles of submitting, revising, (resubmitting,) and publishing do not at all fit within a traditional 12-month calendar. Google Scholar, for example, says that I published 8 articles over the past year. And while that’s true, the bulk of my time was spent working on material that will not see the light of day until next year (or later!). Rather than pushing in new directions, much of my work this year continues along the same pathways I described in last year’s post and the themes I note below should look familiar.

[I realize many of these links may not be accessible if you are not reading this from the hallowed proxy server of a university campus; if you are interested in reading any of the work below, please get in touch.]

Youth Civic Literacy Practices

As the primary theme across my work, I’ve been exploring youth civic literacy practices. Over the summer, Amber Levinson, Emma Gargroetzi, and I published our first set of findings from our analysis of the 2016 Letters to the Next President project. A couple of interviews about this work can be read here and here. We’ve spent significant time exploring this data set and I’m excited about the ways this study challenges existing assumptions about youth civic learning (and if you are a classroom teacher or know one, consider having your students participate in the Letters follow-up, Election 2020: Youth Media Challenge). In addition to this article, we expect to have several other articles related to Letters to the Next President trickle into the public in the coming months.

Nicole Mirra and I have also been exploring civic literacies in collaborative work for several years now. We’ve been slowly constructing a book-length argument about youth civic learning in the context of participatory culture, Trumpism, and high-stakes school evaluation. As one component of this argument, we published an analysis of the framing of civic learning within national policy documents like NAEP and the Common Core. More work in this area should be out next year.

Healing

Though I chipped away at the writing of this article over several years, my essay, “A Call for Healing Teachers: Loss, Ideological Unraveling, and the Healing Gap” was published earlier this year, continuing my focus on the need for teacher healing and challenging the assumptions of what counts as social and emotional learning. As I mentioned earlier, this was one of the most personal pieces of writing I’ve worked on. Along with a couple articles from last year, this work offers something of a conceptual framework on which I’ve been slowly working toward more empirical work around care, healing, and affect in classrooms. Some findings from these studies should be seeing the light of day by early next year.

Analog Play

I’ve continued to explore the learning and literacy practices around tabletop gaming. My article defining tabletop “gaming literacies” was published online earlier this year and is in the current issue of Reading Research Quarterly. Likewise, my co-authored article with Sean Duncan on the lives and deaths of Netrunner came out in Analog Game Studies.

Expansive Digital Literacies

Yes, alongside analog literacies, I am still very much exploring the role of technology and digital platforms. This past year, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Remi Kalir as we studied the literacy practices related to open web annotation. Our article in Journal of Literacy Research can be found here. Likewise, we had a summer-long open review process for our book-length manuscript for MIT Press’s Essential Knowledge Series. We are busily revising this book now (as in I shouldn’t even be blogging right now!) and I expect the book to come out sometime next year.

Playful, Equitable Learning Environments

All of the work I do is, ultimately, about trying to improve the learning experiences for young people and the ways teacher expertise is taken up more broadly. I’ve continued to spend substantial time thinking about project-based learning contexts for English classrooms with the Compose Our World project. Several articles (and a book?!) will likely see the light of day next year. Likewise, several of my advisees and I have been exploring the affordances of learning within the contexts of school busing. The equity dimensions of getting to school—particularly within the stratified contexts of the Silicon Valley—have been striking. We will be sharing some preliminary work from our study at the 2020 AERA conference, with the eye on submitting to journal in April or May.

I had the opportunity to revise and update my conversation with Henry Jenkins for his recently published book of interviews. Though the conversation is ostensibly about Good Reception, the interview probably offers a clear articulation of how all of the threads of play, technology, civics, and literacy I work on push toward equitable learning opportunities for students and teachers.

—

Again, that’s a recap of published “stuff.” As I said at the top, much of my time in 2019 was spent on work that I can accurately link to later. For example, by my count, between three and six books will be published next year that I either co-edited or co-wrote primarily in 2019. (Only one of those titles is currently available for pre-order, but it’s a good ‘un). Those took a lot of time. Likewise, data collection, study design, partnership development, IRB, and all of the other pieces of participating in the systems of academia take a lot of time.

Lastly, as I see a lot of end-of-the-decade recaps across the internet, I’m reminded that around this time a decade ago I was starting to think, in earnest, about the design of my dissertation. In that sense, the current summary of my work on Google Scholar—while inelegant in its presentation—is a near-accounting of my formal published scholarship across the decade. See you all for Coffee Spoons 2020.

“What’s it all for?”: #AERA19 Schedule and Resources

Like much of the rest of the educational research world, I’m in Toronto for the next few days for the annual AERA meeting. I’m sharing my presentation schedule below as well as some resources related to the address I’m giving on Saturday as the recipient of the Jan Hawkins Award. If you’re in town, please send me a tweet and let’s connect!

First, I’ll be speaking and sharing findings from several different elements related to the Letters to the Next President study Amber Levinson, Emma Gargroetzi, and I have been engaged in. Here are three sessions highlighting different aspects of this work:

Additionally, I’ll be in conversations with friends as part of a presidential session on Sunday, “Forging a New Digital Commons: Youth Re-Imagining and Re-Claiming Public Life.”

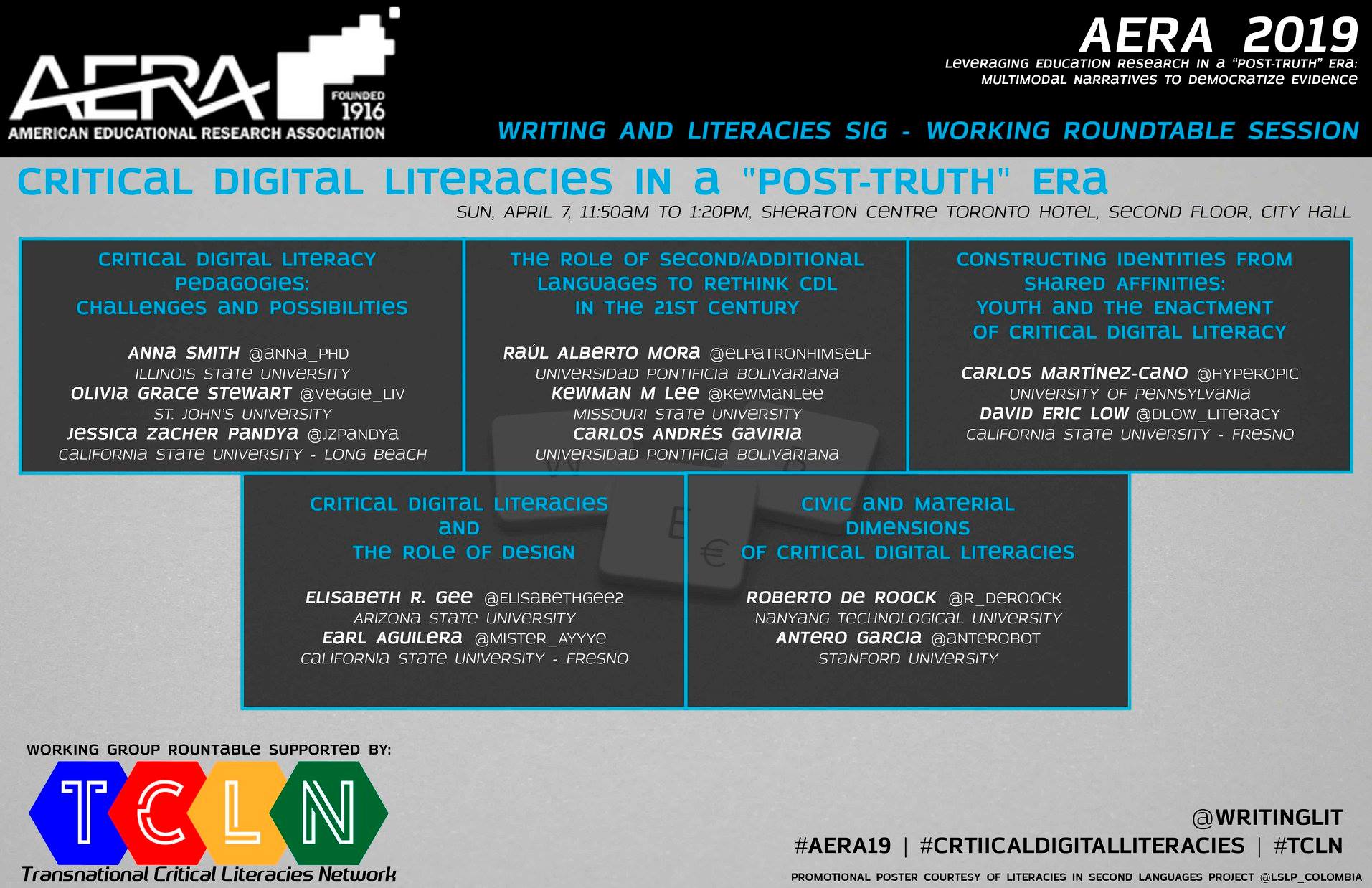

I’m also part of a large crew of amazing critical literacies researchers for a working roundtable session. Raúl Alberto Mora made a flyer for this session:

Finally, on Saturday, I am giving a short address as the recipient of the Jan Hawkins Award. This talk, “electric word life: Learning, Play, and Power in an Era of Trumpism” is based on an in-progress essay that explores researcher responsibilities in an era of oppression and Trumpism. I’m planning on doing this by centering the meaning and history of Prince’s song, “Let’s Go Crazy.”

Hawkins Address Resources:

Because I don’t go deeply into the articles I reference in this address, I’m linking to them here for future reference (please reach out if you need access to any of these articles!):

Garcia & Philip, 2018: “Smoldering in the darkness: contextualizing learning, technology, and politics under the weight of ongoing fear and nationalism”

(This is the introduction to this special issue of Learning, Media and Technology focused on “New Narratives for Solidarity, Resistance, and Indignation: The Intersections of Learning, Technology, & Politics in a Climate of Fear, Oppression”. More info on the whole issue here.)

Garcia, Stamatis, & Kelly, 2018: “Invisible Potential: The Social Contexts of Technology in Three 9th-Grade ELA Classrooms“

Garcia, 2017: “Privilege, Power, and Dungeons & Dragons: How Systems Shape Racial and Gender Identities in Tabletop Role-Playing Games”

In press: “A Call for Healing Teachers: Loss, Ideological Unravelling, and the Healing Gap”

(This article, forthcoming talks about the need for healing in teacher education; I’ll post a link when it is available in the coming weeks. More as background than anything else, here are a few words and stories shared nearly a decade ago on this blog about my father.)

Garcia, 2018: “More than Taking Care: Literacies Research Within Legacies of Harm”

Garcia & Dutro, 2018: “Electing to Heal: Trauma, Healing, and Politics in Classrooms“

Garcia & Gomez, 2018: “Player professional development: A case study of teacher resiliency within a community of practice“

Mirra & Garcia, 2017: “Civic Participation Reimagined: Youth Interrogation and Innovation in the Multimodal Public Sphere“

And, because it feels relevant to the talk. I should share the official archive of Prince gifs. (I couldn’t compete for an audience’s attention with any of these looping during my talk, but hope they are useful for everyone!)

Coffee Spoons 2018: What I Worked on This Year and Why

I’ve been thinking about how opaque the researching/writing/publishing process is for academics. Like most of my colleagues, I did a lot of work this year that is largely invisible and that won’t see the light of day until next year (or later). This often meant digging into data analysis with colleagues, engaging in field work in various cities as well as virtually in online environments, planning, preparing grant reports, and other day-to-day activities that move scholarship forward. It also meant spending a lot of time writing, re-writing, editing, and re-editing. Even when something is accepted for publication, it can be months until it officially reaches the public.

In light of this, I want to highlight some of the research I worked on this year. This is not a definitive list; Google Scholar has a close-to-complete list of the publications I wrote this year and I am sporadically trying to add PDFs of various materials to my Academia page (I don’t love the service, but it’s an easily findable platform where I can put papers until requests for them to be taken down trickle in). Instead, I am hoping this post describes what this research is about, the purposes underscoring my work, and the kinds of social, community, and activist commitments that drive what I do.

Healing, Politics, and Responsibility

In several essays, I focused intentionally on the role of healing, politics, and the responsibilities of researchers. Generally, I have been arguing that emotions are intertwined with politics and that both of these are topics that teachers are not well-equipped for in classrooms; this includes teachers’ own emotions as well as those of their students. Though youth civic identity has been a key part of the work I’ve been doing, this focus on healing and politics comes from my own inability to work in the months after the 2016 presidential election. I have been focusing intentionally on the ways teachers and researchers must account for affect and politics in our work. This article in English Education is probably the clearest distillation of this work for me right now (and that link includes the many crowd-sourced, open web annotations that were collected as part of the Marginal Syllabus). The special issue of Learning, Media and Technology that Thomas Philip and I put together was first developed in early 2017 and digs into these themes as well (it came out three weeks ago, to echo impetus for this post). I’m planning to dig further into these topics in more empirical work in 2019. Likewise, the research on student civic writing practices during the 2016 election are also tied into these themes and I am hoping to share these findings next year.

Reading, Writing, and Technology in Classrooms

I continued to research classroom reading and writing practices—both in articles that came out this year as well as in data still making its way through the publishing pipeline. In general, my colleagues and I have looked at assumptions about technology and what count as reading and writing in classrooms. Classrooms today are shifting in ways that are often overlooked when we think about new advances in technology, classroom interactions, and relationships—the fluidity of video links, of complex learning I’ve been researching. At the same time, the resilience of traditional, factory-model instruction remains staunchly in place. My work in this area tries to push on broader understandings of technology and pitfalls of forcing new contexts into old forms of schooling structures. Further, the ongoing Compose Our World project that I am part of is in its fourth year of data collection and I am excited to begin sharing our work around project-based learning in ELA classrooms soon. Further, I’ve been engaged in a couple of practitioner-facing book projects related to classroom equity in secondary ELA classrooms as well. I am hoping I can share these in the early months of 2019.

Multimodality, Gaming, Analog Interactions, and Digital Literacies

Somewhat related to the above topic, I also spent a substantial amount of time thinking about and troubling notions of sociocultural literacy. This ILA Literacy Leadership Brief is a short synthesis of my push on understanding how technology can meaningfully support students and teachers. The gist is that the emphasis needs to be on people and what we can do in collaboration with one another; hearing, empathizing, and working in solidarity with one another must be centered with tools playing a secondary role. Likewise, like in my chapter in this volume, I’ve been trying to tease out the differences between digital literacies, analog literacies, and gaming literacy practices. Several of my articles have been intentionally pushing toward “analog” literacy practices to guide our field to be more intentional about what we refer to as “digital” literacies and what is overlooked with sweeping, generic terms. Though I didn’t have other gaming-related articles come out this year (they are in the works!), my previous work still managed to piss-off a bunch of gamers.

Related to this scholarship, my frequent collaborator Robyn Seglem and I co-edited a special issue of Theory Into Practice on Multiliteracies. The various pieces in this issue all are pushing on new understandings of literacies as informed by the New London Group’s seminal work (not officially old enough to join us at the bar for a celebratory drink!).

Equity-Driven Design and Methodology

Nicole Mirra and I have been engaged in a bunch of work that pushes on familiar concepts of civic identity, equity, and imagination in classroom and informal learning contexts. In general our work is about broadening how we interpret civic participation, research around it, and engage in models of research that elevate the voices of youth, teachers, and the communities we learn alongside. Though from 2017, this article that Nicole led is a useful position from which we situate a bunch of the articles we have in the works. Somewhat related, my co-authored chapter in this book and in this book and in this book speak to ways that I see research and design intentionally engaging practitioners in this work.

Literature and Pop Culture

I still spend a bunch of my time reading YA books and thinking about comic books and pop culture more broadly. I still don’t think our pedagogies and policies take seriously the role of pop culture in classrooms and this has been a serious area of what I’m investigating. Likewise, when it comes to the role of YA literature, transmedia, and fandom, the burgeoning methodologies in these spaces are awkwardly suited for engaging in spaces of educational research and I’ve been exploring methodological approaches to these spaces; all of this work is still developing right now. The chapter on Cathy’s Book that Bud Hunt and I co-authored was fun to work through and has hints of this thinking. Similarly, I spent a lot of time on a large editing project related to comic books and pedagogy which I hope I can announce in the coming months.

Though not definitive, I think this gives a snapshot of some of what I spent 2018 doing. I also realize that my work can look a little scattershot when described as above. I’ve been trying to work on articulating the driving agenda around youth, identity, and civics that compels me to study PBL in 9th grade classrooms while also thinking about layers of gaming in Dungeons & Dragons while also analyzing student letters to the next presidents; these are all of a piece in my attempt to understand civics and schooling today. Maybe the links across my work will be a little clearer in 2019.