Multiliteracies is an area of interest for me and my classroom, and I am hoping to use this post for dialogue and collective theory-building. But first, I want to talk briefly about being a book geek. As an English teacher, I am passionate about literature. During my first two years in the classroom I overextended myself by maintaining an evening and weekend job assistant managing a popular independent bookstore in Los Angeles.

Passion, Teaching, and Literacy

The pay was paltry and secondary to the opportunity I had at first dibs for advanced readers’ copies of works by my favorite novelists – not to mention engagement with local literati, and the opportunity to discover personal favorites through customer recommendations, fellow employees, and random books falling on my head while shelving the particularly tall bookcases.

I’ve written elsewhere why this kind of passion is a key component to successfully engaging students. Passion is contagious; it was my bookstore co-worker, Nancy, enthusiastically talking about the growing complexities of J.K. Rowling’s work that eventually compelled me to bother breaking the spine and entering the world of Hogwarts.

All of this is to say that I’ve become interested, now as an educator and researcher, into the changing and fluid world of literacy development.

Multiliteracies and Thinking about Literacy beyond 2011

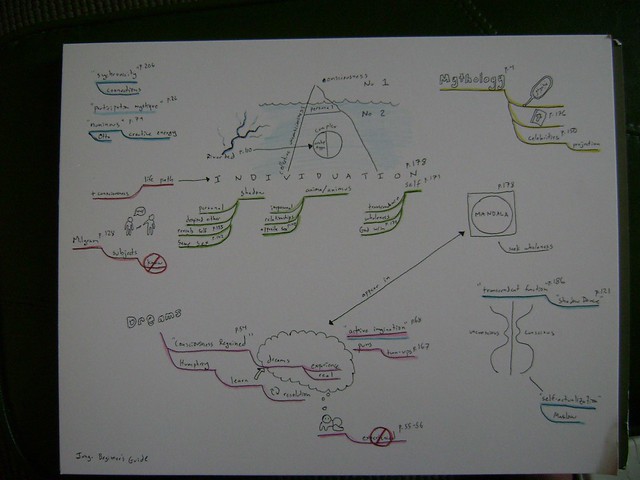

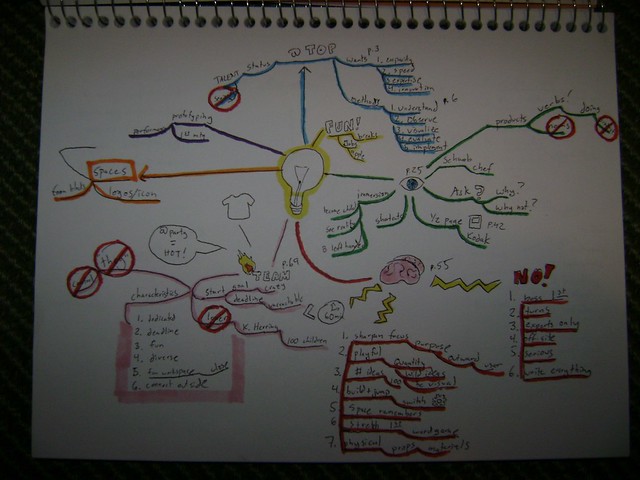

As a 21st century teacher, the work of the New London Group – their conceptualization ofmultiliteracies – is not only a breath of fresh air, but it also liberates my approach to English Language Arts instruction when I guide the learning needs of my ninth graders.

Briefly, the major principles of a multiliteracies framework relate to how technology is fundamentally changing the ways people are communicating: It is bringing people into closer proximity to one another, and the forms of communication in which people engage are multimodal, meaning that they incorporate word, image, video and sound.

And so it was at this year’s American Education Research Association conference last April that I eagerly joined a crowded room to see many members of the New London Group speak in a session titled “Beyond New London: Literacy, Learning and the Design of Social Futures.” And while I was excited about the potential of this session, I left feeling that the researchers, for the most part, didn’t talk about what is happening in literacy development, nor did they update the concept of multiliteracies or point toward reasonable responses to this work.

My interest is, where is literacy heading? What are the implications for the students in my classroom and the literacy achievement gap in general?

Literacies are multitudinous and text is a fluid concept that moves beyond the printed page. This much educators and researchers are generally accepting in this day and age (thank you, New London).

However, in 1996, when “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures” was published, social networks were not a norm, Google did not yet exist (nor did YouTube, Wikipedia, etc.), and mobile media devices were owned and used by an exclusive and small sector of young people. In short, the work does not account for the significant ways young people are interactive and learning today.

I want to outline a few ideas about how I see literacy expanding today. These are initial thoughts and I hope we can engage in collective development around what you may think as well. There are three developments in literacy that are under-recognized in classrooms, in policy, and in empirical learning theory research:

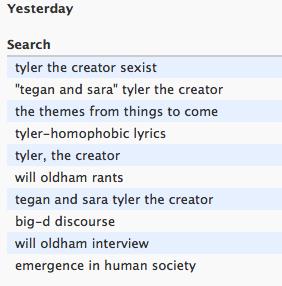

1. Search, Query, and Interpretation

2. Conscious identity development

3. Online/Offline Hybridity and Spatial Interaction

Search, Query, and Interpretation

To effectively navigate, produce, and communicate within the participatory structures both online and offline, students today need to understand the ways that search functions. Black hat & white hat search optimization, for instance is an innately complicated idea that directly impacts what students see and interact with through online spaces. Likewise, the tenets of something like Google’s search algorithm dictate what students are allowed to “find.” In this instance, seemingly ubiquitous engines like Google and Bing act as gatekeepers for counternarratives that are published online but suppressed by a page’s ranking. Douglas Rushkoff’s warning, Program or be Programmed, paves the away for thinking about how students need to be equipped to not only understand why they are seeing the products online when they search academically and recreationally, but also to think about how students can develop search tools for themselves – these computational and programming literacies are going to be the second language acquisition tools students will need to master.

Conscious identity development

Related to interpreting and understanding search-like tools, it is necessary for young people to recognize the way students read and view texts online reifies specific hegemonic ways of being. As a quick example, if students search for images online of their community or a profession they aspire to work within, the images they see dictate an aggregate normative understanding; the narratives online of urban youth perpetuate stereotypes and students should be able to read these narratives critically. Likewise, when students develop and shape online personas inMMORPGs, social networks, and online discourse, they are consciously involved in personal (and sometimes collective) identity development. These literacy practices directly impact the images, words, videos, and other myriad media products that a larger and larger public sees and interprets vis-a-vis youth identity.

Online/Offline Hybridism and Spatial Interaction

Finally, and perhaps what most teachers are seeing within their classrooms, students are utilizing online tools to mediate predominantly offline relationships. When students are texting in my classroom or posting updates to their Facebook pages, they are doing so mainly to maintain a closeness to peers and friends are usually interacting with on a daily basis. Students mediate their day-to-day physical world decisions through online tools. This hybrid media interaction is a space that is becoming more and more persistent in classrooms. Asking a group of my 9th graders if they text or are on Facebook as frequently during lunch or after school, the students rolled their eyes incredulously: of course not – they are busy socializing with the friends they’ve been texting and communicating with when they were supposed to be silent reading in my classroom.

Collaborating Around a new Framework

Without the New London research and much that has since followed, this conversation would not be anchored within meaningful discourse. I am hoping for this to be the start of an ongoing formation of post-New London Theory building. I am interested in the space where this work can be done.

Fifteen years ago, when the authors of “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies” met at the New London site, they purposely published their article in the Harvard Education Review without their names attached. Though the identity of the authors of the piece was not a conspiratorial secret, the gesture is significant. I am hoping those individuals interested in participating in shaping a renewed framework of multiliteracies can comment below and we can discuss an open space for this conversation to continue. Ultimately, I’d hope for a group of us to share this work’s developments in a future post & perhaps wherever else this work can directly impact classroom practices and research.