It’s been just over a month since I stopped working at Manual Arts, the high school where I spent the past eight years trying to cut my teeth as a teacher; the place where I probably learned more every day than I was privileged to teach. And while I’ve been spending my time since packing–and later unpacking–boxes, standing in line at a new (though just as slow) DMV, and figuring out how to at least somewhat safely operate a circular saw, this primarily offline time has afforded me the opportunity to reflect on this final year at Manual Arts and what that school space has meant to me.

In many ways, leaving this school–particularly in light of this last year–has been filled with sadness-tinged relief. It makes me uncomfortable to say that, so let me explain where this feeling is coming from.

I should make it clear, though, that despite any of the challenges I’ve faced or dealt with at Manual Arts, I feel extremely, extremely privileged to have been able to be a teacher there. The students that I’ve worked with have pushed me in ways that this rant will not encompass. In a moment, I plan to share the more troubling challenges at Manual Arts but want to make sure that my gratitude to the abundant experiences of joy and enlightenment I’ve had from my students and colleagues is noted.

I’ve made it no secret that Manual Arts has had its fair share of challenges over the years. From truancy policies that essentially criminalize students to the fact that my eight years at this school has included eight different principals, Manual Arts, structurally is a persistent mess.

Last August, I met my eighth principal for the school. Robert Whitman was assuming his first head principalship at Manual having been an assistant principal at several other local urban schools prior. I want to stop here for a moment and note that this is par for the course of urban school leadership in Los Angeles: the schools most in need of strong leadership according to district metrics like standardized test scores, teacher turnover rates, and dropout levels act as training grounds for principals. The majority of the principals that have left Manual Arts while I was there spent little more than a year (sometimes less) letting the school coast while adding their new leadership position to their resumes and quickly taking a job at a less demanding school.

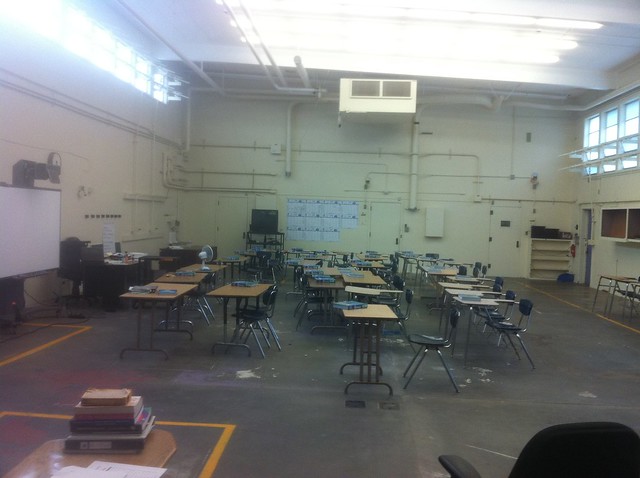

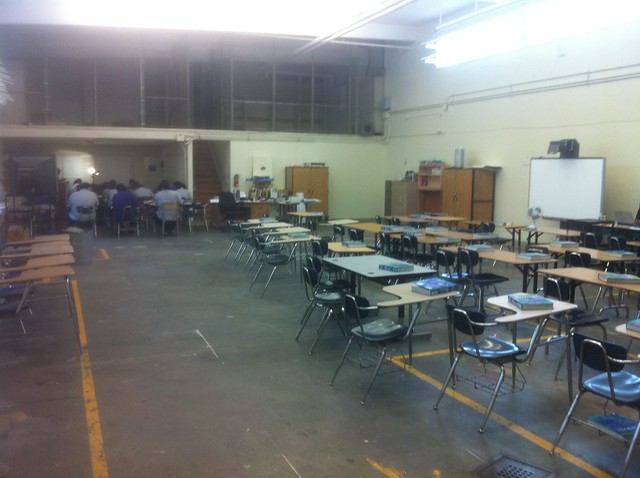

The new principal’s challenges were compounded by the fact that the school moved from a three track year-round schedule to a traditional calendar. While the three track system meant longer school days and is generally inequitable for all of the students involved, it was at least a routine students and teachers had learned to cope with for the decade plus that Manual Arts was a year round school. And while time was stabilized as a result of the move to a traditional calendar, all else was disregarded: class sizes shot up well beyond what teachers or classrooms were equipped to deal with. Across the board, students were packed 36-40+ students deep in core instructional classes. Strangely, our security and deans at the school were gutted. Here’s an equation for disaster at even the best of schools: too many kids with too little supervision equals dismal instruction.

Of course, the instability of varied leadership and strategies takes its toll on the students and teachers of Manual Arts. The Freshman Preparatory Academy–the school’s effort two principals before Whitman–was an effective effort in sustaining student interest during the year our students are most at risk of dropping out. With a new regime of administrators and a general lack of institutional memory to drive the decisions of the school this year, the majority of the practices that supported ninth grade teachers were decimated. The halls of FPA, where I spent most of my time helping teachers with technology challenges at the school became chaos. Even the most collaborative teachers I was privileged to work with went into all-out-survival mode, trying to get through the overcrowded classes one day at a time.

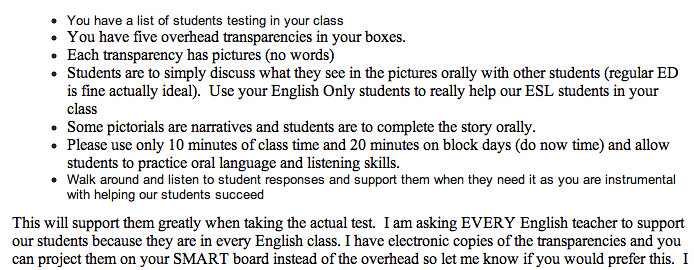

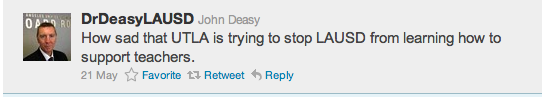

The administration, like LAUSD’s superintendent’s phrase, shifted to a “laser-like focus” on skills and test preparation. The execution of this focus, however, was generally incompetent. My former guiding teacher and one of the most innovative educators I’ve been privileged to work with was subject to no less than a year-long procession of passive-aggressive administrators observing and encouraging him to volunteer to pilot the Scholastic Read 180 program in his classroom. The experience sapped him of the enthusiastic energy I typically got to see in him and seemed like a contract-protected form of administrative bullying. (I assure you I have no problem with being observed–under the best of administrators my practice has significantly grown from administrative observation. What this teacher underwent felt possibly retaliatory for the way he has been outspoken on the school’s campus.)

As a quick aside: as I type this, my former advisor forwarded me her emailed “word of the day” and it is fitting to today’s discussion.

Quantophrenia: “Undue reliance on or use of facts that can be quantified or analyzed using mathematical or statistical methods; inappropriate application of such methods, es. In the fields of sociology and anthropology.”

Nearly all of the teachers I’ve come to work with closely and that I’ve learned from are voluntarily leaving Manual next year. Most of them have helped co-design the Schools for Community Action and are trying to make these new schools (just down the street from Manual Arts) a more humane alternative to the bureaucracy that has plagued Manual Arts this past year and long, long before.

I say “voluntarily” in the previous paragraph somewhat uncomfortably. None of these teachers want to leave the students at the school. As is the case in school after school, Manual’s problems are adult-driven.

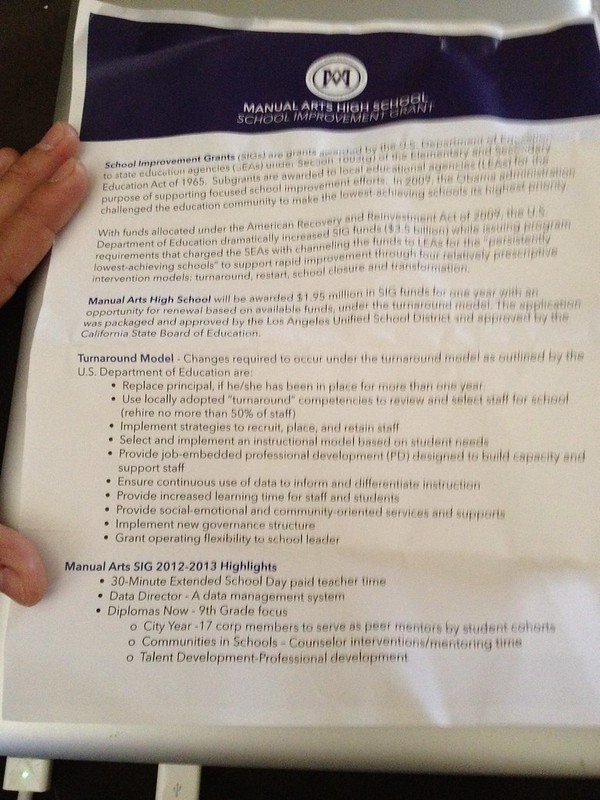

Perhaps what’s driven me to this reflection more than anything else is an announcement that was made during my last week at Manual Arts: the school has been awarded a School Improvement Grant for next year as a “turnaround model.” What this means is that the school is being reconstituted. “Reconstitution” is fancy ed-speak that essentially means that everyone at the school is being fired and needs to reapply for their jobs. Everyone, that is, except that in this single instance the principal will be keeping his job without reapplying. Wait, what? Yeah, that happened. Oh yeah, one other thing: in this particular concoction of reconstitution, the school will only hire back 50% of the teachers that choose to reapply at Manual Arts. This is clearly an opportunity to clean house and ensure that the bad apples in the eye of the nascent principal and less-than-effective management company, LA’s Promise don’t come back.

Here’s the fancy color-printed handout that teachers received notifying them of the reconstitution. Sure looks expensive to have printed out the school’s logo in color: a sound decision, I’m sure.

I should make it clear that money is great: the million plus dollars that the School Improvement Grant can bring to the school can make a real difference in the outcomes of the students at Manual Arts. But you know what else can make a difference? Positively driven, motivated teachers that know and have been involved in a school community. I should note, too, that even when working on school wide reforms in the past and reconstitution was invoked, I could not find significant research that it leads to positive academic outcomes.

So: sadness and relief. The work conditions at Manual have become untenable in a way that has made such an archaic word to me feel positively spritely. I’m genuinely saddened that the school I’ve invested so much time and energy in and that has rewarded me again and again with happiness and the best of my teaching experiences has been denigrated by inconstancy and poor management. I’m saddened that I left the school under these conditions. And, as awful as it may be for the students there, I am relieved not to be there next year. Even if they would have hired me back.

Tell people this is awesome: