Pretty great trailer:

Pretty great trailer:

Teaching ninth graders, the past month has been one centered around themes of conflict as my class analyzes Romeo and Juliet. Over this and a couple of future posts, I wanted to share some of the work my students and I have been engaging in. Essentially, the role of the seminal, ninth grade text, has shifted. No longer can students simply read and analyze Romeo and Juliet. Instead, it is not an option to include materials that exist outside of the original text; it is an imperative part of understanding the text. I’ll return to this idea after sharing some examples.

Utilizing the Flip Cams that Peter and I used for our What Son Productions course, the students will be recreating their own versions of scenes from the play. This is not an original or a very creative idea (more about that in a minute). What is interesting, though, is the process of reading Romeo and Juliet across different interpretations. As we read a scene, we may screen a scene from the 1996 Lurhmann interpretation as well as the 1968 Zeffirelli interpretation. We are then utilizing a 4×4 graphic organizer to note key differences between the original source, two films, and our own ideas of how the scene could be produced. These products are becoming the basis for a production log the students are creating as they note where one version may fall short – Tybalt being too aggressive to Romeo in the 1996 version before Mercutio becomes a “grave man,” for instance.

As I mentioned, the concept of asking students to recreate their own versions of scenes isn’t a very new one. In fact, as more and more students have easy access to tools of production – as these tools have become ubiquitous – it’s easy to see student work samples online. However, the vast, vast majority of these samples appear to be from overwhelmingly white communities. And these versions are taking significant liberties in their portrayal of urban reenactments of Romeo and Juliet.

Over the course of a week, I began each class by screening a 3-7 minute YouTube clip. I simply searched “Gangster Romeo and Juliet” and a deluge of student-created videos showed up showing “ghetto” versions of the play. [This was inspired by a conversation about developing this unit with my colleague Peter Carlson.]

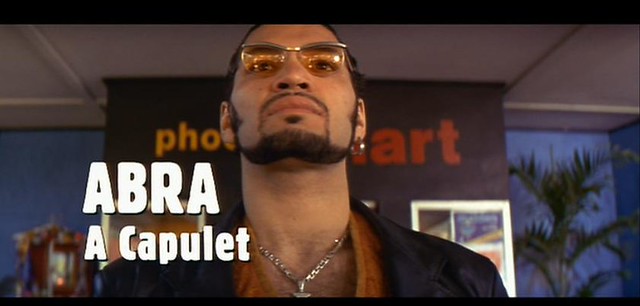

This ghetto, however, is technically the community my students live and go to school in. This ghetto is stereotyped by white students in ways that at first issued guffaws. My students found the videos funny at first. However, after a couple of days, students said they felt “mocked.” They said that the videos didn’t show things correctly, were making fun of the community, and actually lacked textual understanding of Shakespeare’s words (several of the films, for instance, abbreviated Abraham’s name the same way that Luhrmann’s did).

Often times, these videos are posing these ghetto versions in lush, rural or suburban communities:

I want to underscore that I am not using these examples to criticize the students that have made them. However, when discussing them with students, we have noticed that there are not similar “ghetto” versions made by people of color. And if they are not creating them, essentially, an incorrect truth about what the ghetto is and how people act within it is being reified. My students shifted uncomfortably in their seats as they began thinking about the messages that a critical mass of lighthearted “ghetto” student clips are sending; these paired with YouTube clips of student fights are furthering stereotypes of student behavior and expectations.

As educators, our role is changing; the power of student production is a necessary tool for critical analysis. How can these tools break down existing assumptions?

As a class, my students are thinking about how they can create videos that respond critically to the samples they’ve seen, accurately reflect a nuanced understanding of their neighborhoods & worldviews, and express thematic interpretation of the canonical text. It is the necessary hard work I am excited about seeing develop in the next two weeks.

Again, as I said in the opening paragraph, the role of Romeo and Juliet is much more inclusive than simply the 92 pages of the Dover edition that my students have each been asked to purchase. The culture and understanding of the text is inclusive of a rich body of knowledge, assumptions, and continuing dialogue with the work through writing, acting, and recording. Social networking, new media, and a changing access to technology means that simply summarizing plot and theme is disregarding the other critical skills students need to learn in an English class.

First of all my good friend and filmmaker Dehanza Rogers is currently trying to raise funding for her magical-realist, Haitian short film, Lwa. Please take a look at her Kickstarter page. Really, even a small contribution will go a long way to helping support a filmmaker I believe in.

Over the next couple of weeks, Daye and I are reading through Edwidge Danticat’s latest collection of essays, Create Dangerously, and have agreed to post a few comments back and forth. We did this once before a while ago and it’s not too late for you to grab a copy and join us as we read at the accommodating, glacial pace of two chapters a week. [Though I know Daye’s familiar with Danticat’s work, this collection got my attention via this post.]

For me, I am reading this book largely oblivious to the Haitian culture from which Danticat is writing and I’m hoping to use this dialogue as a space to understand better both the space of art from which both Danticat and Daye are producing from and within.

I’m struck by the fact that the titles of the first two chapters of the book serve as gentle and opposing commands: “Create Dangerously” and “Walk Straight.” As if the role of the “Immigrant Artist at Work” traverses the careful balance of producing with criticality and toeing an existing conceit. An interesting balancing act; I know how this tension is played out in the public eye for Danticat based on her reflections in “Walk Straight.” Daye, I’m curious how you are working between both of these.

As for the content, I like the way Danticat’s own perspectives as a creator are steeped in a history –familial, national, cultural, universal. The Haitian political figures that begin the book, the subterfugre, assassinations, and secret police reminded me Graham Greene’s lesser work, The Comedians and I was pleased to see Danticat reference it directly (as well as Greene’s exile from Hatia as a result of his choice of dangerously creating the accurate portrayl of the dictatoriship within the novel). [As a brief aside, I want to point out that I purchased The Comedians as a used bookstore solely because of a blind faith in Greene’s writing and the incredible cover art.] I am struck by the idea that, “there is probably no such thing as an immigrant artist in this globalized age.” While I don’t necessarily agree with Danticat’s claim here, I am curious about what authorial advantages are gained by vantage of the “immigrant” in the flattened world so many are pointing to.

I don’t want to make this too long as Daye and I will be checking in over the course of the book, so I’ll end by examining a quote from the second chapter: “Anguished by my own sense of guilt, I often reply feebly that in writing what I do, I exploit no one more than myself.” I’ve find myself empathizing with Danticat’s claim here and wonder how you, Daye, see this quote in relation to your own work and in particular to Lwa.

There’s a lot of talk about Waiting for Superman: what it gets wrong, what it portrays incorrectly, what needs to be done. Having finally seen it, I actually can’t say I’m all that disappointed with the film. If anything, I see it as a tremendous opportunity.

Sure, I take issue with the ways that charters are lionized, unions are vilified, and lottery-losing parents are victimized in Waiting for Superman. However, as an educator, I can say I’m still genuinely glad this film is making headlines. I realize this idea may upset many of my colleagues, but I hope more people will see it. I hope they’ll walk out of the theater angry.

Scanning the credits, I noted that Waiting for Superman utilized a data set and resources I am not only familiar with but know and trust the researchers that created it. As such, it’s not that the film is menacing propaganda but more a gripping reminder of the ways that data can be framed to tell specific narratives. Of course, when such tales deal with the opportunities and lived experiences of young people across the country, the stories matter much much less than actual results.

I appreciate efforts like Not Waiting for Superman and I hope more people will be able to look at some of the more level headed responses coming out of the film. And frankly, the amount of funding that can go directly into classrooms as a result of the Donors Choose promotion with the film is fantastic. If anything, I feel like a lot of individuals are going to walk out of the theater and many will be compelled to visit the film’s web site, maybe click the Take Action tab, maybe even buy the more problematic companion text. And critical educators are going to stomp their feet and make this a debate when it should be a dialogue.

Here is a film that is helping create vitriol for the atrocities that are happening – historically – within classrooms. This is an opportunity to build coalitions around anger – not see the film as an attack but as an entry point for more dialogue and for action regardless of if you are pro-Waiting or pro-Not Waiting. Frankly, it would be great if a site like Waiting for Superman and a site like Not Waiting for Superman simply linked individuals to the exact same forum – everyone will be going to these sites for the same purposes: students.

[If you would like a PDF of the above info to distribute, it is available here.]

Over the past two weeks, approximately forty students from Manual Art have participated in a film intersession course I am co-teaching with Peter Carlson. These students have watched a handful of universally lauded films, critiqued them, and created & produced their own films. And although Peter and I will be writing in more detail about the pedagogy and instructional experiences of our current intersession film class, I wanted share a few snippets of what makes this such a fun class to be a part of.

Again, I will be posting an update about the upcoming film festival, Peter and I will be drafting a more comprehensive description of the work, and I am hoping to rope in a few students to author posts about their experiences as well. Stay Tuned.

I wanted to share a couple of recent videos that I’ve been rewatching.

First, while I don’t agree with all of Jane McGonigal’s arguments, I’m genuinely excited by her recent TED talk. At this point, I am strongly aligned with the idea of connecting game play to real world change. You could do a lot worse than spend 20 minutes watching Margolis’ presentation.

I’ve been following Jane’s work since Greg Niemeyer showed me World Without Oil (A bit of trivia: Greg was also one of the members of Jane’s dissertation committee). Her article, “Why I Love Bees” fits directly into my research on the Black Cloud. Similarly, Evoke seems like an interesting premise. And while I understand what she’s doing with her argument by contrasting the time youth spends playing video games with the time they spend in schools, I think this is where a lot of researchers are missing a big opportunity. As a field, we continue to look at the informal environments for game play and research. It’s easier to do so – a select group of interested individuals, less controlled curriculum, easier access issues, etc. However, think about how the power of game play for change could be compounded within formal learning environments. I’m working on developing material around this within my classroom, and expect game play to fit somewhat prominently into my dissertation. So if it sounds like I’m grandstanding or being a bit presumptuous here, it’s more personal throat-clearing than anything else.

Second, I just saw We Live in Public and found it to be an absolutely compelling and terrifying documentary. I’m not clear about what disqualified it for an Oscar nomination, but think it could have given The Cove a run for its money. The foundational arguments about privacy, surveillance and our culture’s relationship with the media are extemely prescient. As I continue to think about how student-generate media products will be created, shared, and assessed within my classroom, these are the topics I am concerned about. Ownership of data, of our lives, and of conceptions of propriety is in flux and the experiments that Josh Harris challenges us to face this fact.

His next project sounds equally as preposterous as past efforts, and I’m interested (if not extremely wary) about what will transpire if he gets the funding for this. Though I encourage you to watch his pitch below, I highly recommend seeking out and viewing We Live In Public for a better sense of context.

As problematic as Avatar was, it was still a fun flick. The incredibly clunky script didn’t bother me nearly as much as the score and the font used for the subtitles.

In any case, when James Cameron wasn’t busy hitting you over the head with the environmental and colonial no-no themes, there were occasional moments of subtlety.

I like the notion of the film as a testament of experiential knowledge over book knowledge. Reading about and learning the language of one culture does not make you the kind of authentic participant than actually, y’know, participating does.

Not too shabby a blockbuster for the winter season, and I always hoped they’d remake Dances With Wolves, so there you go. Would fit nicely into a unit with Ishmael, Thoreau, or even Siddhartha.

I’ve been trying for some time to track down the new Babies documentary trailer, after first seeing it before Where the Wild Things Are. I remembered feeling troubled by the way the film other-izes and makes cute foreign lifestyles and traditions.

I’m not trying to be curmudgeonly and express distaste for everything, but it feels odd when everyone in the theater is laughing at African and Asian babies (“Ha ha, they’re fighting” and “Ha ha, they have a goat that’s drinking the bath water”) while the whiter babies are simply seen as adorable, as normal.

It doesn’t look like this was the intention of the film or the trailer, but – when we’re filming & editing from a westernized position (I believe the film is French) – these biases arise unintentionally.

I think the trailer will have to be online soon. In the meantime, I snapped a bunch of pics in the theater as I watched Fantastic Mr. Fox as if I were some bootlegger trying to peddle wares in the LA Santee market.

Check out the contrast in depiction of lifestyles (yes, perhaps this is partly the point of the film, but doesn’t it make it even more problematic?). Enjoy.

I realize you may not be able to hear me over the general choir of groaning that this post will explore current reality television, but I assure you, there is some good news here.

I’ve now seen the first two episodes of the current season of the Real World, where not 7, but 8 lucky twenty-somethings get picked to live together to see what happens when people stop being polite blah blah blah.

What’s most interesting in this season is that – at least in these first two hours – the show has deemphasized the sex-crazed shenanigans of the past half-dozen seasons. Instead, the group is diversified to a point beyond any kind of legitimate “real” world. However, thrown in with the very straight-laced metro-sexual Mormon, the aspiring dancer, the guy with the abs, and the guy with Iraq-related PTSD, are a gay man (who used to train dolphins at Sea World – awesome), a girl that – up until her present relationship – used to date women exclusively, and a transgendered woman.

Looking at that roster, that’s a pretty hefty dose of sexuality for our impressionable youth. I couldn’t be happier. In these first shows, it’s interesting how the show is edited; clearly the two gentlemen that are not used to/comfortable around homosexuality are coming off the worse for wear. Their reactions and types of jokes they make are clearly supposed to be “not funny” to viewers at home. The way they speculated about their transgendered roommate – going as far at one point as referring to her as “it” – isn’t something that they’ll be getting praise for after the season is over. And when one of these guys is pecked on the lips by a drag queen at a gay bar, the way he violently wipes his lips and looks disgusted is downright upsetting (though this, unlike the other examples, is contrasted with the delighted cackles of the rest of the roommates).

Sure, the show is likely to devolve into fights, hook-ups, and tears in the coming episodes. However, for now, the Real World is opening up concepts of – and flat-out endorsing – tolerance for the millions watching the show. That’s got to be worth something, right?