A couple weeks ago, I got an email from a fellow teacher, Jason Sellers. We’d met several months ago while I was in Orlando for NCTE and he for the National Writing Project’s annual conference. Jason is a high school English teacher in Staunton, IL, a rural high school 45 minutes outside of St. Louis. He’s also a NWP Technology Liaison with the Piasa Bluffs Writing Project, a member of the Cultural Landscapes Collaboratory (an organization that provides professional development to schools), a Hill Country blues guitarist, a motorcycle adventurer, and an MMA fighter.

Discussing the ways we get tied up with information, we thought it would be useful to share out some ways we are organizing, synthesizing, and being able to just remember the myriad information strands we are engaging with on a day-to-day basis. Below we begin our discussion of academic productivity.

How do you manage the information you read in books for future reference?

Jason:

Here are possible options I’ve explored: purchasing traditional books and writing in the margins; purchasing e-books and using Kindle’s highlight feature to save passages; taking snapshots of passages with my cell phone and saving them in EverNote; taking notes in a journal; creating mindmaps.

My main reason for leaning towards ebooks and/or saving passages in Evernote is that I feel books will inevitably move to an electronic format. I don’t want to have to comb through my collection of paper books for marginalia, which I’ll then have to convert to digital format.

The problem with margin writing and ebooks is that they both require purchasing the book. I can’t write in books from the library, and pirated e-books are difficult to find online (waiting on the book equivalent of Napster). Ultimitely, I ruled these two options out, because I’m poor.

I prefer to check books out from the library. I tried taking snapshots of passages of library books with my cell phone. This may be a good method, but I have an older model of cell phone with a crappy camera — doesn’t capture text very well. Someone with an iPhone might be more successful doing this.

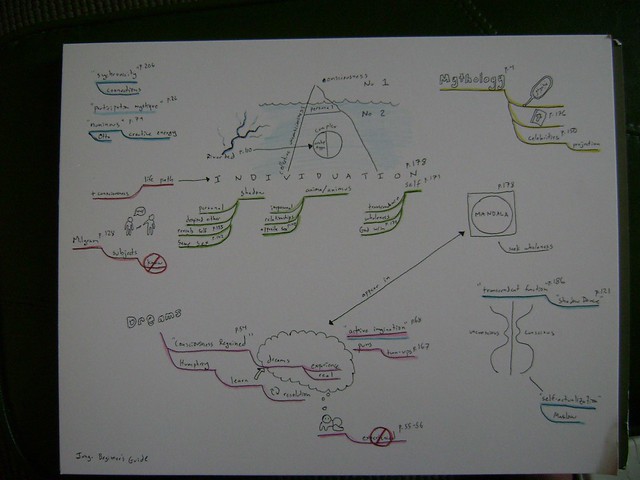

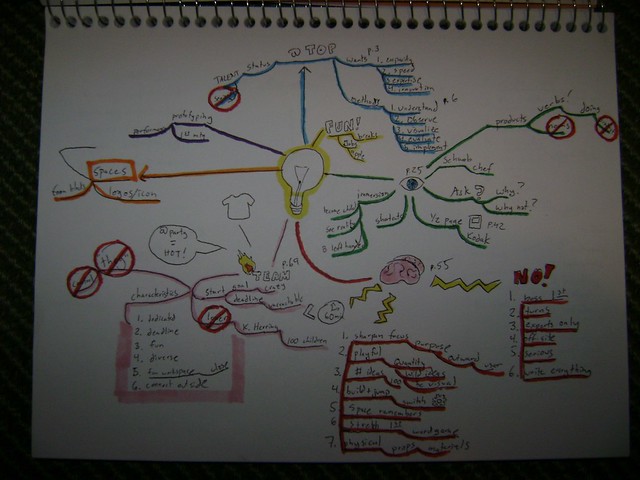

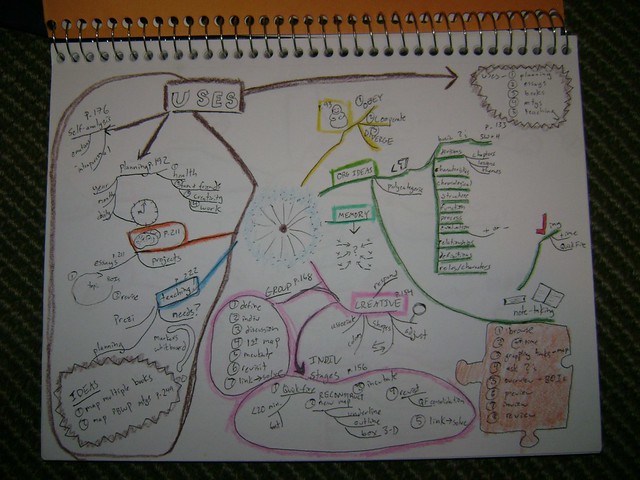

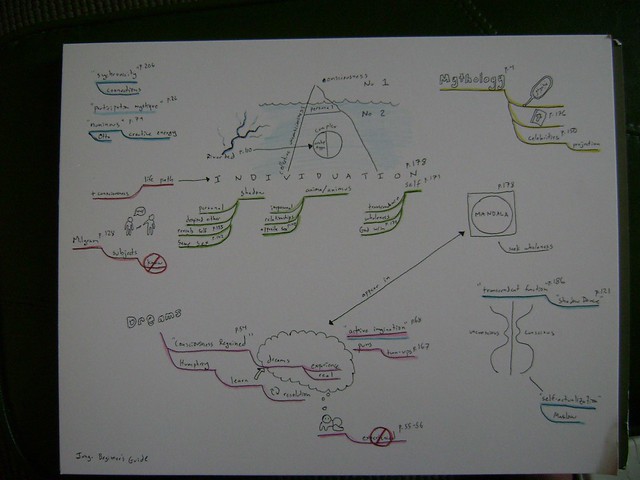

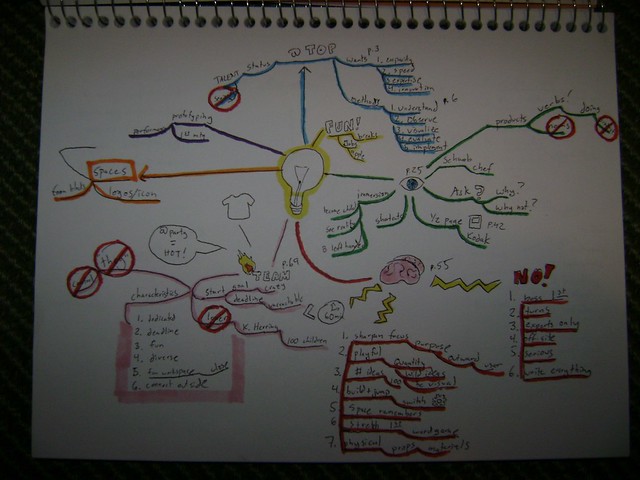

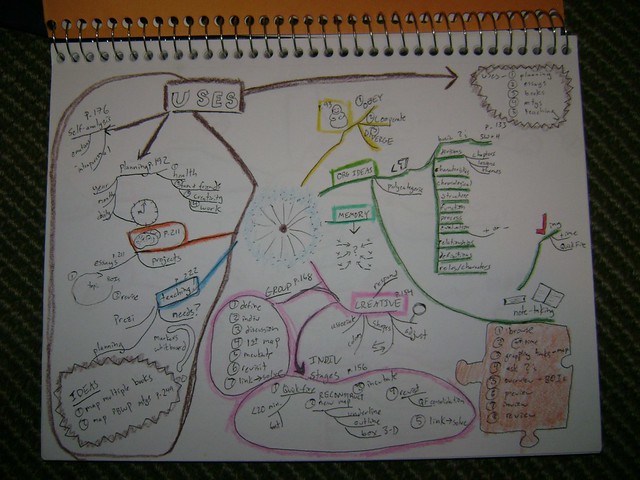

The best method I’ve found for retaining information in books is to mindmap the book. I’ve been using this method that past two months after reading Tony Buzan’s The Mind Map Book. I keep a 8.5″ x 11″ sketchbook with me while I read, and make notes with page numbers for quick reference. That way, I have all the information on one page. Single words and short phrases are enough for me to remember whatever it is I need to remember, and page #s help me track down the passage if I need to cite it directly.

When I finish a mind map, I take a photo, upload it to EverNote, and tag it. Easy to find, and EverNote recognizes handwriting, so it’s searachable.

Thanks again for starting off this discussion Jason. I’m definitely interested in finding out more about other people’s research and creative practices (and hope a few of you will share in the comments below).

As for me, if I’m reading generally, I do a lot of annotating in most books (with exceptions noted below). I also compile a note-taking sheet at the back of most books that allows me to reference back to specific topics and pages I think will come in handy later on.

If I’m reading for a specific project, I’ll also probably start typing my notes or direct quotations as they become prevalent. As I’ve talked about before, Scrivener is an essential note-taking tool for me and for how I organize work related stuff. If there are quotes, passages, or main ideas I want to draw upon or puzzle through, I will type those directly into Scrivener for later–they may get discarded, they may get expanded, they may lead to another book and to another ad naseum, but the point is to get them to the general “space” to which they are related.

I have a pretty strict but impractical approach to writing in books that I’ve been stuck with since beginning my undergraduate work. Basically, any literary, YA, or leisure reading text gets a kind of no-writing embargo placed on it. I’ll admit that the materialistic part of me appreciates the book as a product, especially Books So Ridiculously Awesome You Don’t Even Know What To Do With Them (BSRAYDEKWTDWT). I’ve amassed a handful of first editions of books that have felt important to me at one point in my life or another, and I’ll buy more than one edition of a book to have a “reader’s copy” of a book I don’t feel comfortable risking getting tattered by borrowers of books. Geek Love, Infinite Jest (though the second printing with Vollmann’s name correctly spelled, unfortunately), and–come to mention it–a healthy portion of Bill’s books as well:

Now, when it comes to academic texts, many get put through the wringer, as do books that are often drawn upon or which it’s a good idea to keep in a back pocket once in a while – some of Salinger’s books fit in this category and I’ve probably bought or given away a copy of Franny and Zooey on an annual basis.

The tricky thing for me is when a book straddles the line between work and play (Dewey reminds us that this is a false divide in the first place). So, having to read House of Leaves for an undergraduate seminar, made me struggle between writing in and not annotating (this sometimes leads me to do things like buy two copies of a book … I am not proud of this).

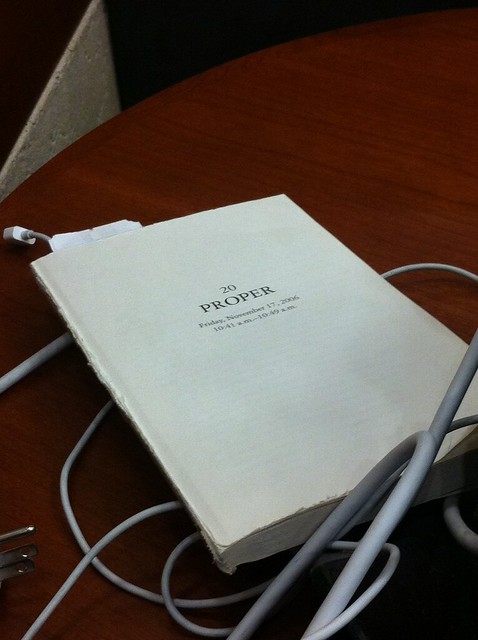

As for non-fiction, every page and inch of the book is fair game in terms of annotation. Some of my critical theory books are difficult to read due to third and fourth rounds of annotations. In general, however, the very last page of the book becomes a pseudo-index for me of pages, phrases, and ideas I may want to reference at some time in the future. The page is usually very sloppy may have notes to random people, doodling, and references to things that may not make sense to me. It’s pretty common for me to be unable to decipher some of these notes later on – the fact that many of these books are at least partly read in cars and on airplanes makes the notes that much messier. Here’s the back page of this book that I read last week:

Again, very random notes and jottings. However, considering that the majority of my academic books have similar pages, my library very quickly is distilled to a handful of pages that I can cull together around specific projects. It leaves me in the midst of an unfinished conversation I can pick up and add to very quickly.

So that’s a snapshot of two approaches to digesting reading materials. What are your approaches? I think we’ll, eventually, work through our approaches to writing, organizing, and moving from others’ work to our own. This reflective practice reminded me of this and I hope this can be a way to think about the different approaches pedagogues and researchers take in engaging with the mental labor of educating America.

Tell people this is awesome: