Over the past couple of days, I’ve been reading Bringing Innovation to School: Empowering Students to Thrive in a Changing World. The book pleasantly showed up in my mailbox over the weekend. It’s author, Suzie Boss, is a prolific blogger and journalist around issues of education and has, on a couple of occasions, asked me to share projects like the Black Cloud. As a result (and full disclosure here), I make a couple of brief cameos in Bringing Innovation to School.

Her book and my work with CDAGS has me thinking about the challenges of sustaining teacher innovation in today’s era of standardization. Suzie agreed to answer a handful of questions about her book and ways to support innovation via email. And, since I’m sure you have much more insightful questions than I do, I encourage you to tweet questions and reactions to the book to @suzieboss.

I want to thank Suzie for her time going over these questions with me. And, as you read over this, I would challenge educators to think about: how would you share the ways you innovate? What challenges do you face and how are you innovating around them?

Why did you want to write Bringing Innovation to School? Where did the impetus come from?

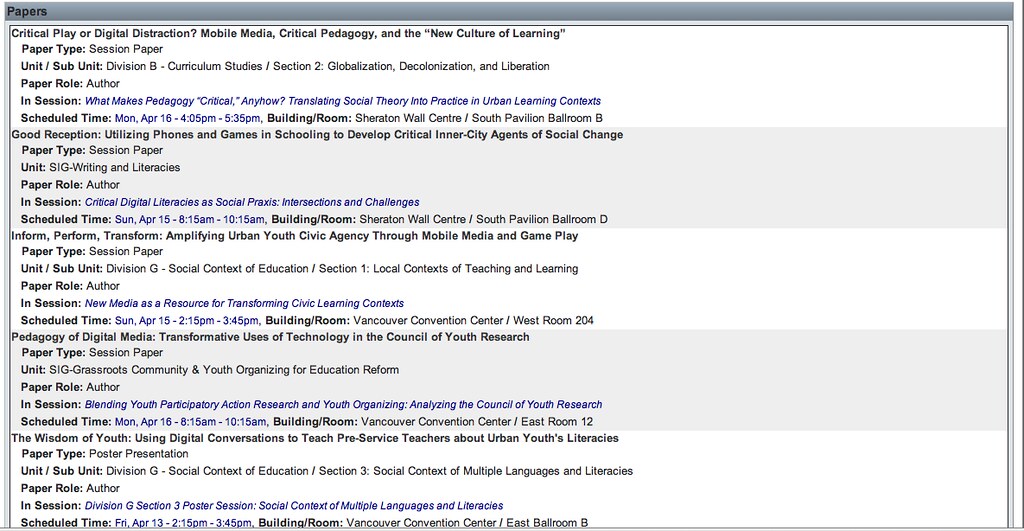

This book grew out of writing and consulting I’ve been doing for the last several years. I spend a lot of time talking with and writing about innovative teachers, the ones who design learning experiences that open up the world for their students. (Your Black Cloud project is a good example, Antero.) For audiences outside the K-12 field, I often write about global innovators who are tackling some of the world’s toughest problems—clean drinking water, illiteracy, climate change, poverty. So what do K-12 education and social change have in common? More than you might guess. When I talk with social entrepreneurs, I hear them describe the same problem-solving strategies that work well in project-based learning. This book is an attempt to bring these two “worlds” together and offer some fresh ideas about how we can prepare today’s students to become tomorrow’s creative problem solvers.

I’ve been seeing the idea of innovation in schools being defined primarily by folks outside of schools – the i3 grants, for instance. I’m wondering if you can help break down what you mean by “innovation” and what it means specifically for teachers?

Innovation is often easiest to spot after it happens. It might be the breakthrough product or new idea that we didn’t know we were waiting for. Once it comes along, we don’t want to go back. (Would you replace your laptop with a manual typewriter?) But innovation involves more than consumer products. It’s an approach to problem-solving that can be applied to any sector to create a “new normal.” For teachers, it’s worth knowing that innovation is not only powerful but also teachable. We may think that breakthrough ideas come about through some kind of alchemy. That’s seldom the case. When you look at the back story of an innovative idea, you tend to find a familiar process at work. It’s a process that students can learn and then apply to tackling any kind of problem. For teachers, it’s worth remembering that innovation involves both thinking and doing. Give students opportunities to generate solutions and then put their ideas to work in practical ways.

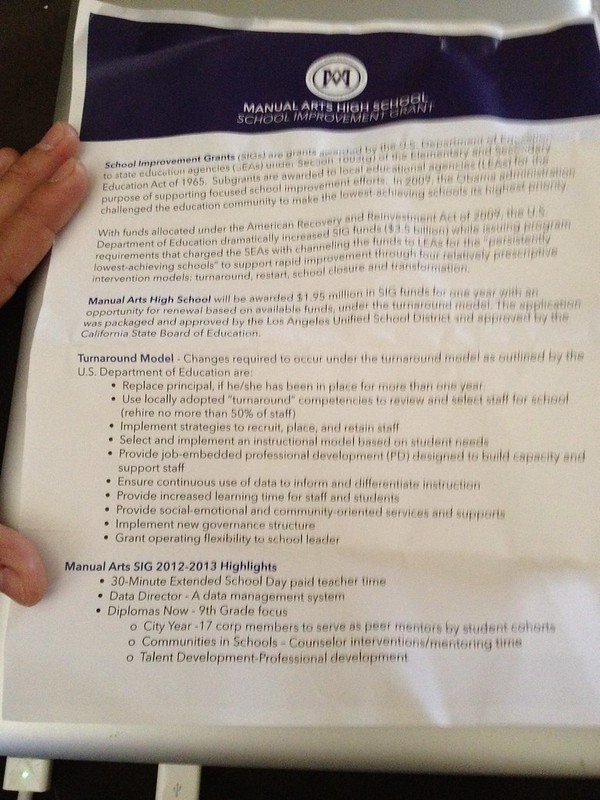

The conversations I have with teachers in Los Angeles are often rooted in feelings of frustration. Particularly at Manual Arts, teachers felt like they were being blocked from being able to innovate or create exciting experiences for their students. What are the barriers schools are facing? What kinds of advice do you offer?

I hear you. Plenty of teachers are rightly frustrated by obstacles that get in the way of innovation. They might face an expectation to stick to scripted instruction or lack access to the technology tools that students need to connect and create. In the book, I challenge school leaders to think about how they foster or hinder innovation. One of the action steps I suggest is finding allies who share the goal of developing a new generation of innovators. It’s also important to showcase success when it happens. Let others see what your students are capable to doing and creating when given the opportunity. We can also do much more to encourage a “fail safe” learning environment. Innovators don’t fear failure. They learn from it.

Without giving away all of your book’s findings, can you share a couple of ways educators are sparking in-school innovation? Also, some of your earlier work focuses on project based learning. I’m wondering if you can talk briefly about the connection – is PBL innovative?

Project-based learning doesn’t guarantee that students will be innovators, but good projects can set the stage for innovation to happen. For example, the book takes a close look at one project in which students designed an inexpensive water purification system for villagers in Haiti. It has all the elements of high-quality PBL, including core academic content, teamwork, research, problem solving, and public presentations of learning. But it goes beyond what we see in typical projects. These students were determined to “go big.” Leveraging their communication skills, they raised funds to travel to Haiti, install the devices, and teach villagers how to maintain them so they will have a sustainable source of clean drinking water. The project expanded from one science class to engage the entire district, plus many community members. Part of innovative thinking is knowing how to engage others in your good ideas. These students figured that out—and they’ll never forget what they accomplished. Throughout the book, there are many more examples of projects that start with a strong PBL foundation and build in opportunities for students to take risks, learn from mistakes, and put good ideas into action.

Finally, I’ve been thinking lately around the challenges of teacher training and professional development. Is innovation something you think can be taught to teachers? How can principals and administrators support teacher innovation?

Early in the book, I encourage teachers and school leaders to think about their own innovation profile. Are they action oriented? Do they know how to network? Can they look ahead to imagine the benefits of new ideas? School leaders need to encourage these traits, in themselves as well as in their staff, if they’re serious about developing a new generation of innovators. We can also offer teachers professional development experiences that let them learn and practice the process of innovation. I did a lot of field work for this book. One of my most enjoyable experiences was taking part in an innovation workshop for teachers at the Henry Ford Learning Institute in Detroit. It was immersive, energizing, instructive, challenging—and fun. How often does professional development feel like that?