Carlos, Roach, Mutiny?: What is Travis Teaching?

Leave a reply

Mark recorded an on-the-fly interview with one of my 9th graders on one of the few days that he’s been on campus. To say that he’s been someone I’ve struggled to connect with is an understatement. I really appreciate Mark’s prodding and the student’s candid reflections. However, even as he notes his self-defeating actions, I question where we (Mark, myself, his other teachers past and present) could have done better. What are the structures in place and the policies enforced that made it possible — easy even — for this student to choose to slip by?

Within a year and a half, LA Times columnist Sandy Banks has written three columns about reform efforts at Manual Arts High School. Specifically, the three articles are all focused on my school’s managing partner organization, LA’s Promise (previously MLA Partner Schools).

When the first article was released, my students responded critically to the changing conditions at the school.

As I’ve written about before, the LA Times continues to muddle and depersonalize my school’s tenuous path forward.

While the jury is still out regarding what education will look like at Manual Arts next year, I am intrigued by the way these three stories read side-by-side. So much and so little have changed. More importantly, I am interested in putting these articles in front of the people they are written about – my students – and having them look at how their school is being discussed by adults. What would students think about Banks’ continued gaze from afar at education in South Central? How would they interpret the social and political implications of her continued analysis?

Hey LA Times, I was reading you online today and noticed this.

It’s funny how this is news today. Remember how, like, two weeks ago, I blogged about Manual arts, our 32 RIFs, and included an image of the exact same demonstration? I guess not.

Oh, and while we’re at it, I was just wondering why you don’t really bother mentioning anything related to this.

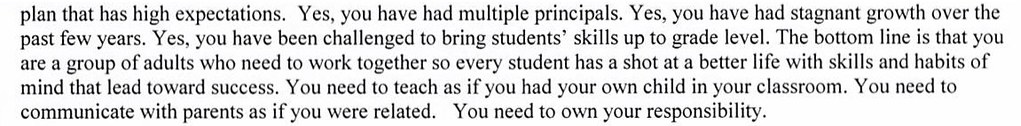

In regards to the previous post, the following excerpt of a letter sent from the superintendent to the school faculty does little to illuminate how our school … proceeds.

This is going to sound overly pessimistic and cynical, but it’s hard to read an article like this and not grit my teeth.

The anecdotal stories of layoffs are a useful tactic to maybe get the public to understand that there are faces and names to the teachers that are continuing to be cut and villainized in the current political rhetoric.

However, the article points to the inequity of cuts and to the general (more than usual) messy situation of layoffs in LAUSD. Hamilton students are in tears and parents are shocked by the loss of teachers they loved. This is something new for these students.

At Manual Arts, I want to applaud the continuing efforts of students to fight for teachers they are losing. But the picture is muddy and isn’t getting clearer any faster.

Here’s what would have been different if Steve Lopez had written about Manual Arts:

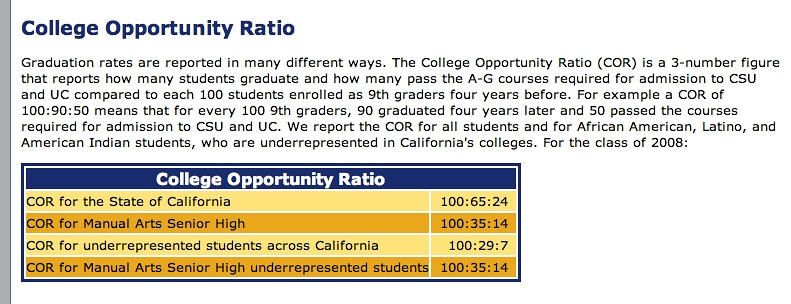

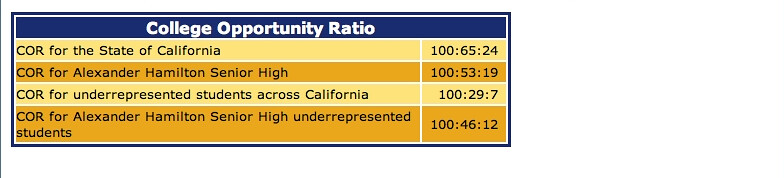

And before reading further, you might want to compare the general data–particularly the College Opportunity Ratio (COR)–for Hamilton and Manual Arts to see how these RIFs will play out.

Both images come from the UCLA IDEA’s California Educational Opportunity Report.

A Timeline for Dummies

Manual Arts is also a great microcosm of the mess in the district. If you want to know what the plight of public education looks like, here’s my best play-by-play of how it’s played out in … oh six months at my school:

November: Our sixth principal in the six years I’ve been here quits. [This is a highly politicized event that divides the campus. To leave things simple: I felt that Principal Irving was an effective leader in his professional role and I see his departure as a loss for our students. Not everyone will agree with me.]

December: Rumors of reconstitution and heavy RIF numbers are shared in weekly union meetings. It becomes clear that the QEIA grant funding that was paying for nearly 20 teachers and other faculty positions at the school is not being renewed next year. [This is a highly politicized event that divides the campus: some teachers blame our school’s network partner and leadership staff for the fact that we did not meet benchmarks that we set. Some teachers blame the school district for imposing benchmarks on us that we did not meet. In any case, these are real jobs that we had saved with these funds… because of these saved jobs, it looks like Manual Arts did not have a lot of RIFd teachers at our school, which directly impacts what happens as a result of … the Reed Settlement.]

January: The Reed Settlement is Approved. Anticipating the many layoffs that will likely occur under the current doomsday budget, 45 schools that would be impacted the most are placed on a list that would protect them. [This is a highly politicized event that divides union. To leave things simple: the settlement protects RIFd teachers at some schools but disrupts campuses that are not typically affected by these layoffs – schools in affluent in communities, schools that don’t have newer teachers, school that are probably doing academically better … probably schools like Hamilton High School.

[Oh yeah, despite being either the lowest or second lowest performing school in the district (depending on if you count Jordan’s missing API data from last year) … Manual Arts was NOT on the list of protected schools. Our administrative team was efficient enough in the past with shielding our staff from layoffs that we did not look like a school that will need to be protected. Instead the RIFs from other schools will burden our school on top of the RIFs we will already have. This will be very bad as we shall see.]

February: District RIF projections are around 5,000 teachers, we are told our school will move to a traditional calendar, Manual Arts is requested to create a plan to show the superintendent why we should not be reconstituted–all staff reapply for positions. [This is a highly politicized event that divides the campus. Several teachers–myself included–are seen as colluding with our network partner and are not seen as trustworthy.]

March 8: One of our network partners, WestEd, announces that they will not be involved with our campus in the near future. [This is a highly politicized event that divides our campus. Blame is placed on our other network partner.]

March 11: At an afterschool faculty meeting, our teachers are told that we will have 32 RIF teachers. In addition, (and partly because we are going to a traditional calendar) we are losing 50 other teachers, 10 long-term sub positions, and 8 district intern teachers. Yes, we are losing 100 out of 190 teachers. Oh yeah, and our expected enrollment next year is anticipated to be the same.

March 15: 32 Manual Arts teachers receive certified mail letters that let them know they are being laid off next year; they are neither surprised nor clear about what this means in terms of what will actually happen (RIFs are projected and some are rescinded in the past). Steve Lopez writes about the shock at Hamilton High School.

March 18: Students begin demonstrating at Manual Arts. Reports of walkouts and sit-ins trickle into texts and facebook updates throughout the day. [Update: brief coverage of student efforts here.]

Without adding too much more commentary, I want to point out how the snowball has been rolling into an avalanche throughout the year. Morale, unsurprisingly, is at an all time low at our school; we are still a big question mark in terms of our future. It could be minutes or days until we know about if our school is reconstituted. A mass exodus of teachers–those RIFd and those that have just had enough–is expected at the end of the year. I also want to point out how all of these events are layered in meaning. With each major announcement, the school roils in finger pointing. Calls for unity are voiced; a union election is wedged throughout all of this, as are the Public School Choice results, as is an election that affects the School Board, as is a new incoming Superintendent next month, as is an ongoing attack on unions and public education. The results compound rhetoric and confusion. At the end of the day, how will any of this help the 3400 students that will be walking into our classrooms at Manual Arts next year. Or tomorrow?

Teaching ninth graders, the past month has been one centered around themes of conflict as my class analyzes Romeo and Juliet. Over this and a couple of future posts, I wanted to share some of the work my students and I have been engaging in. Essentially, the role of the seminal, ninth grade text, has shifted. No longer can students simply read and analyze Romeo and Juliet. Instead, it is not an option to include materials that exist outside of the original text; it is an imperative part of understanding the text. I’ll return to this idea after sharing some examples.

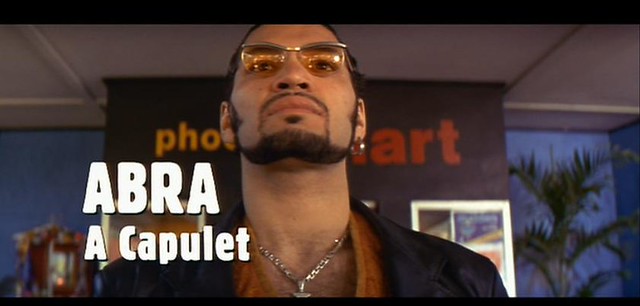

Utilizing the Flip Cams that Peter and I used for our What Son Productions course, the students will be recreating their own versions of scenes from the play. This is not an original or a very creative idea (more about that in a minute). What is interesting, though, is the process of reading Romeo and Juliet across different interpretations. As we read a scene, we may screen a scene from the 1996 Lurhmann interpretation as well as the 1968 Zeffirelli interpretation. We are then utilizing a 4×4 graphic organizer to note key differences between the original source, two films, and our own ideas of how the scene could be produced. These products are becoming the basis for a production log the students are creating as they note where one version may fall short – Tybalt being too aggressive to Romeo in the 1996 version before Mercutio becomes a “grave man,” for instance.

As I mentioned, the concept of asking students to recreate their own versions of scenes isn’t a very new one. In fact, as more and more students have easy access to tools of production – as these tools have become ubiquitous – it’s easy to see student work samples online. However, the vast, vast majority of these samples appear to be from overwhelmingly white communities. And these versions are taking significant liberties in their portrayal of urban reenactments of Romeo and Juliet.

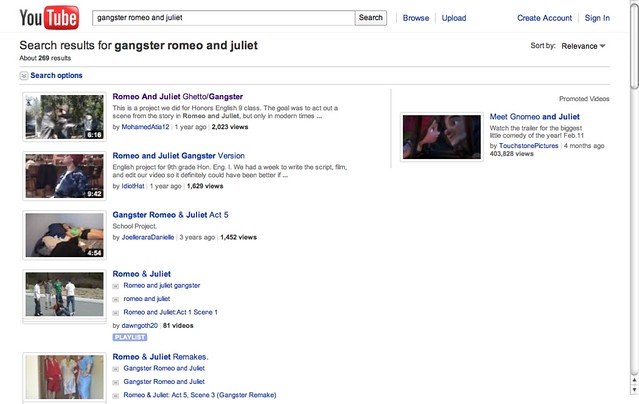

Over the course of a week, I began each class by screening a 3-7 minute YouTube clip. I simply searched “Gangster Romeo and Juliet” and a deluge of student-created videos showed up showing “ghetto” versions of the play. [This was inspired by a conversation about developing this unit with my colleague Peter Carlson.]

This ghetto, however, is technically the community my students live and go to school in. This ghetto is stereotyped by white students in ways that at first issued guffaws. My students found the videos funny at first. However, after a couple of days, students said they felt “mocked.” They said that the videos didn’t show things correctly, were making fun of the community, and actually lacked textual understanding of Shakespeare’s words (several of the films, for instance, abbreviated Abraham’s name the same way that Luhrmann’s did).

Often times, these videos are posing these ghetto versions in lush, rural or suburban communities:

I want to underscore that I am not using these examples to criticize the students that have made them. However, when discussing them with students, we have noticed that there are not similar “ghetto” versions made by people of color. And if they are not creating them, essentially, an incorrect truth about what the ghetto is and how people act within it is being reified. My students shifted uncomfortably in their seats as they began thinking about the messages that a critical mass of lighthearted “ghetto” student clips are sending; these paired with YouTube clips of student fights are furthering stereotypes of student behavior and expectations.

As educators, our role is changing; the power of student production is a necessary tool for critical analysis. How can these tools break down existing assumptions?

As a class, my students are thinking about how they can create videos that respond critically to the samples they’ve seen, accurately reflect a nuanced understanding of their neighborhoods & worldviews, and express thematic interpretation of the canonical text. It is the necessary hard work I am excited about seeing develop in the next two weeks.

Again, as I said in the opening paragraph, the role of Romeo and Juliet is much more inclusive than simply the 92 pages of the Dover edition that my students have each been asked to purchase. The culture and understanding of the text is inclusive of a rich body of knowledge, assumptions, and continuing dialogue with the work through writing, acting, and recording. Social networking, new media, and a changing access to technology means that simply summarizing plot and theme is disregarding the other critical skills students need to learn in an English class.

So tomorrow and Wednesday my school will administer the California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE). In the past, there has been concern that some students have not taken the test “seriously.” Some of my past seniors, in fact, have retaken the test because they said they simply raced through it because it felt inconsequential (even though they need to pass it to officially graduate).

However, when I look at the work in my classroom and data from other measurements at the school, it’s pretty clear that many, many of the students have a lot of academic strides to make before they can pass the test. While participation and engagement may be part of the challenges our students face, quality instruction is probably most important.

Which is why the following excerpt from a faculty email is so problematic:

Every Student Who Passes a CAHSEE Test Earns a Prize as follows:

Proficient on Both Sections = iPad, IPod Touch, iPod Shuffle or $20 gift card

Proficient on 1 and Pass on Other Section = iPod Touch, iPod Shuffle, or $20 gift card

Pass on Both = iPod Shuffle or $20 gift card

Pass on 1 section = Gift Cards of $5-$20

Remember to tell your students a Pass Score is 350, and a Proficient Score is 380.

Additionally, another Small Learning Community (SLC) teacher emailed the following:

To [specific SLC] Teachers

Please remind our [SLC] 10th grade students that are taking the CAHSEE for the first time, and score proficient on both the math and english, they will receive $50.00.

They must score proficient on both tests. Also, we will raffle a pair of tickets to the Laker game February 22nd, as well as, other prizes for [SLC] students who show up both days and

show a sincere effort while taking the exam.

Hoping the best for all our students.

To me, it would be one thing to reward participation on the exam. However, when students are being rewarded (beyond intrinsic rewards) for passing the exam, it creates a false hierarchy on campus. My prediction: the students in the magnet academy, the NAI program, and a handful of students in AP & the honors tracks will clean up and get lots of rewards and the students that need the most academic support will feel deficient. There is some (problematic) support to the notion of paying students to get good grades. However, this differs significantly from performing on a single test over a two day period. We may be trying to reward diligence and participation, but the model looks–to me–like we’re instead penalizing struggling students for systemic poor teaching.

– So what kind of book do you want to read?

– I want to read about someone getting stabbed … but not in jail.

– Hmmm okay, let’s see…

– Or I’ll just read Charlotte’s Web.

I was already jotting out notes in response to this article in the New York Times about iPads in the classroom, but Cathy Davidson’s response captures my sentiments.

I will say that the $1 million plus that my school is spending on laptops and smart-boards is a similar, if less trendy, example of utilizing new technology to reinforce archaic classroom structures. If we aren’t using the tools for new modes of learning, if we aren’t reinventing the classroom space and experience, we are subverting student potential with shiny gadgets. Just last week, Kanye inspired me to write about this exact problem:

Is it really the best we can do to simply duplicate textbooks and textbook practices when equipping students with iPads and mobile devices? Screen reduced to nothing more than digital page?