Hubris: What is Travis Teaching?

2 Replies

So I’m kinda into The Voice. A week in a hotel + Hulu = completely caught up and officially rooting for Beverly.

I was hooked by the blindfolded recruitment phase. In some ways it reminds me of the process of entering the realm of academia: reviewing writing and intellectual ephemera, top-of-the-field professors recruit graduate students to join their teams (these teams will eventually duke it out in academic journals and conferences around geeky topics). And just like the two ladies on Team Blake, sometimes grad students have to sing backup for their advisors.

In any case, I appreciate the strong representation of LGBT contestants not being tokenized as merely gay. For a superficial talent show, the Voice is doing a great job of presenting its contestants as humanly multifaceted. We’ll see what happens when contestants are voted only by a mainstream public next week.

And though it’s not necessarily tied solely to The Voice, this show is the apotheosis of participatory media’s integration into mainstream broadcasting. The show’s logo is shown as a hashtag throughout the show, the hosts mention when artists are “trending” on Twitter, which performers topped the iTunes charts, and coaches & contestants alike answer questions submitted via social network sites. The integration is not secondary to the show and is a sign of where television is moving.

It was day four of a week long intense standards writing session. As Sandy and I reviewed documents to look at how we were presenting technology in the standards, Barb came in cradling her laptop like a fallen comrade. It had fallen and a crack in the display rendered the computer all but useless.

The screen, however, hemorrhaged spectacular blips of light. When another committee member pressed the screen with a forefinger, the screen spewed color like a fountain of brilliance. As much as I felt bad about the loss of work for the group and of personal equipment for Barb, I was transfixed.

A husband in another timezone was called by one committee member. An LCD was pulled out to reroute the computer’s display. My own productivity came to a halt.

As the majority of us stood around prodding and suggesting and generally not able to do a whole lot about the situation, I was reminded of the calamities that befell the travelers in the Apple II rendition of the Oregon Trail of my youth. Is this the Oregon Trail of the Digital Era? Had our axle broken? Had we failed to successfully ford the river? Improperly squandered our resources?

[This post is shared, intended for, and written as a resource at the Digital Is site for the National Writing Project. If – for some silly reason – you haven’t been over there, please take a look.]

Reading the article, “Press X for Beer Bottle: On L.A. Noir,” by Tom Bissell I was left with several significant thoughts and questions about the role of video games on learning, media, and how we teach storytelling and writing.

Though quite lengthy, I encourage you to read through this resource – though the comments below can be read as a stand alone reflection on video games at large, the review is a useful case-study of how narrative shifts in storytelling affect player freedom and understanding of choice.

What’s at the heartof this inquiry is a tension that exists between video games and story. Specifically, can a video game act as a useful means to convey narrative? As an English teacher and as a writer, I question whether my intentions as a writer – to recount a specific narrative, to persuade and effectively defend a thesis – can be adequately represented in a video game. And even if these ideas are in a game, will it ultimately be a fun one?

A popular game series many of my students (and youth around the world play) is the Grand Theft Auto saga. In these, players may undertake specific missions driving around cities to meet various objectives sand move up the ranks in a city’s organized crime underbelly. At the same time, however, most of my students usually play the game with a more broad understanding of the game’s purpose: cause as much chaos as possible. Driving over pedestrians, getting into glorified shoot outs with law enforcement, creating spectacular crashes, explosions, and city-wide damage, most of my students appreciate the game platform as a space for exploration and play. It is a giant sandbox filled with digitalized violence. Your ethical concerns aside, I question how the developers (writers) of these games feel about this approach. Clearly, there is a loose narrative that students are supposed to adhere to. Clearly, most of them do not.

I should make it clear that I think this is okay. The freedom to resist narrative and to resist societal conventions (to specifically push against them) is exactly what makes these games so engaging for young people…and probably cause the kinds of fear mongering about violence and video games that are monthly headlines in grocery-store magazine displays.

However, the developers of the Grand Theft Auto series have recently released a new game. L.A. Noire (as detailed in the article). In it, opportunities for chaos still can be found. However, this game has a very specific narrative vision. It adheres to traditional storytelling narrative arches. There are things like denouement in its final moments. But with this narrative comes a much more limited scope of choice. The player, though posed with options and-at times a broad area to play and explore-ultimately must take specific paths, choices, and steps in order to proceed. In fact, the game doesn’t really provide much choice at all.

As creating games becomes easier and cheaper, it will become the kind of literacy practice that – I imagine – will be second nature in ELA classrooms in the near future. If this holds true, what kinds of lessons do we develop about teaching choice, agency, and power within video game design?

Similarly, in addition to looking at images of race and class and literary elements in video games, how do we get students to write and think critically about agency and power when they play these games? In essence, by playing a game, a player is essentially committed to a programmed contract that forces them to adhere to the rules, laws, and conventions of social behavior that are designed into the game’s architecture.

This may seem like a superficial discussion, but I caution us, as educators, to think specifically about what video games inculcate in students about power, authority and the way they understand & synthesize information. By garroting a game’s scope, its designer is afforded the freedom to closely “tell” a narrative. However, it will take more innovative game design for a video game to allow open ended exploration that can “show” a narrative based on player free will. This tension between choice and narrative is one that needs to be conveyed in our lesson plans and in our classrooms. How we design our classrooms, establish class rules, and set agendas are no different than digital walls and required button mashing in the stereotypical first person shooter our students play daily.

Mark recorded an on-the-fly interview with one of my 9th graders on one of the few days that he’s been on campus. To say that he’s been someone I’ve struggled to connect with is an understatement. I really appreciate Mark’s prodding and the student’s candid reflections. However, even as he notes his self-defeating actions, I question where we (Mark, myself, his other teachers past and present) could have done better. What are the structures in place and the policies enforced that made it possible — easy even — for this student to choose to slip by?

[post title and “de-centering” in general is being adapted from language in this book.]

In the past month, a typical conversation with me usually involves bitcoins [relax, I’ll explain these in a minute].

It typically involves bitcoins and hyperbole.

It typically goes something like this:

– Hey [interrupting and changing the topic of conversation abruptly] – have you heard of bitcoins?

– No.

– I hadn’t either until recently. I’m basically trying to find someone to tell me why I shouldn’t invest in them, because they sounds like they’re going to kinda take over the world.

– What are they…

What Are they?

That’s where I get confused… I’m not really sure.

As I read more about them and follow random message boards the best I can get is that a bitcoin is a digital currency. Here’s a great, digestible video about bitcoins:

So what?

So here’s the thing: a bitcoin isn’t tied to any government, is constantly limited in quantity (theoretically making them steadily increase in value over time) and can be traded anonymously.

There’s a whole bunch of technical stuff behind all of this and the market of exchange for bitcoins is so small that single investors can regularly change the value of a bitcoin – in the past week I saw the value of a bitcoin jump from $6 to over $30.

[Edit 6/13: and Boom! a day after posting, the Economist writes a feature on bitcoins.]

Why does this matter?

Last month, the U.S. government effectively shut down online poker playing within the country. I know this because it happened while I was playing (I was supposed to be writing… but don’t worry about that). One minute I’m in a hand of limit hold-em, running outside to check the mail and the next, I come back to find out I am no longer weclomed at this table. Because I am playing with U.S. dollars, the U.S. government and its laws control what I do and what kinds of activities I engage in. Sure, I get it.

However, what happens when we de-center money from government?

The short answer is I don’t know … and I bet it can be problematic. Already there are smatterings of articles about the fact that bitcoins can (and in some cases are) being used to buy almost anything – from Alpaca socks to illicit drugs.

Again, no one person or entity controls or owns bitcoins. I am sure various national governments are keeping an eye on the fledging efforts to democratize currency (especially as a bi-product of bitcoins, namecoins, make currency tied even more closely to personal control).

So Here’s the Thing – Time for Some Ed. Talk

In the past publishing was controlled by nations and (much later) large corporations. McLuhan makes clear the nationalistic purposes the printing press played in reifing specific traits and identity within a nascent print-literate nation.

What’s happened to how we engage with writing, literature, and the nature of publishing now that the internet has made it a “free” enterprise? As we see explosions in creativity, expansion in discourse, and newly entangled struggles between old-world copyright and new-world Creative Commons-like control, one thing is certain: cutting the tether between publishing and a select few corporate entities has profound paragidm shifts on culture, interaction, and learning.

Bitcoins – whether they take off or a rival product emerges – are poised to do the same thing for currency that the internet has done for publishing. How much more do we shift toward a Temporary Autonomous Zone (T.A.Z.) when we are no longer held to ordained commerce?

And here’s where I’m more concerned: even if bitcoins don’t take off, I’ve been thinking about an educational parallel. What happens to education when it too becomes decentered from specific forms of government and definitions of citizenship? I write this not from a purely anarchistic perspective. My research is largely concerned with civic engagement and how young people formulate or understand their own civic identity. What happens to democratic education when it is also democratized? Perhaps this is a shift toward a TAZ of educational reform – instead of districts tied to cities, states, and the country, schooles may be aligned to principles, common interests, etc. And where do standards fit into this? Perhaps more than anywhere else, we see educational standards continue to play the role the printing press did in the sixteenth century – without standards, do our schools lose their identity as “American”? Is this necessarily a bad thing? We’re not exactly talking coins anymore, are we? The premise of a bitcoin, however, is what’s begun this line of thought for me.

Presently, I have my finger poised above the equivalent of the “buy” button on Mt. Gox (the central site for exchange of bitcoins) – I don’t know what’s going to come of it, but I’m curious enough to exchange a capital I know well for one I don’t if it means getting to participate in a new mode of exchange.

Just a quick heads up (and record keeping for myself): I have a new post at DML Central about my problem with the word “new” in new media.

If you’ve been working on a paper, proposal, or syllabus lately you’ve probably already heard this rant.

The U.S. Department of Education has just released Local Labor Management Relationships as a Vehicle to Advance Reform, a collaborative report of twelve case studies highlighting Labor & Management collaboration for student achievement. Along with an incredible cadre of educators, I was privileged to write one of these case studies. Centered around work and ideas shared at a summit that took place in Denver in February, the report’s abstract, as printed on this page, follows. Thank you Jonathan Eckert for an incredible job editing and compiling this work over the past three months.

In February 2011, the U.S. Department of Education (ED)—along with co‐sponsors from the American Association of School Administrators, the American Federation of Teachers, the Council of the Great City Schools, the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, the National Education Association, and the National School Boards Association—brought together over 150 school districts at a conference called “Advancing Student Achievement Through Labor Management Collaboration.” Twelve districts noteworthy for the partnership of their district, board, and teacher organization facilitated conversations with district leaders and others in attendance at the conference. This paper attempts to capture what these noteworthy local partnerships have accomplished and, more importantly, how they accomplished it. ED commissioned present and former Teaching Ambassador Fellows, teachers selected for one‐year leadership assignments, to conduct this work. The fellows used interviews, document analysis, and digital audio recordings of presentations made by district leaders to learn from the opportunities and challenges, the successes and missteps of these 12 district partnerships. The introduction to the paper, written by Jonathan Eckert, Professor of Education at Wheaton College, synthesizes the patterns in both the work being done by the districts and how they are doing it.

I’ve been disappointed with my union lately.

That’s a difficult thing for me to say in the current teacher and union-bashing climate. However, while I support unionized teaching labor, I don’t feel like my union (both at the my specific school site and the district at large) has made decisions that are in the best interest of “rank-and-file” teachers. And yes, a union is as strong as its members, so I accept the criticism that comes with speaking ill of one’s own organization.

I say this all as a prelude to point to a useful contrast between my union’s online presence and that of the management it negotiates and works with (or against, depending on the day of the week).

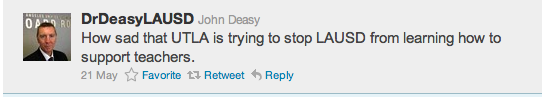

Exhibit A:

And Exhibit B:

Really, UTLA? 2009? Back-patting our own demonstration through a series of tweets? Really? That’s our best use of social media? Meanwhile, Deasy not only communicates an issue clearly, he does so in a way that calls for support and empathy from teachers and the public alike. Regardless of where you may stand on the actual issue at hand, Deasy leverages social media to more effectively inform and sway a population.

Exhibit C:

Unless someone else in UTLA is following other users, UTLA is missing the boat big time with the people they are “following” – this is a huge opportunity to engage, interact, and personalize the union for thousands of its members, instead of merely deferring and following mothership accounts.

Exhibit D:

Really? A broken link for the (once again) 2009 twitter handle?

Discussing this with colleagues at lunch today, I mainly expressed frustration that this is so backwards in our district. I’ve come to see Twitter (through the many news headlines in the last few years) as a tool for working class activism. It is a free, easy, and proven way to mobilize many (many) people. It’s hard to speak hyperbolically about the potential of Twitter; it has literally broken the news about global revolutions.

And yet, instead of UTLA “getting it,” the superintendent beats us to the punch.

And while this can be rectified, this is a useful turning point for thinking about the lessons we teach in our classrooms. If we want to work toward a libratory education, understanding the potential of a tool like Twitter and how to implement effective use needs to become a necessary aspect of education. Clearly, @utla2009 is a useful demonstration of ineffective participatory literacy practices.

Lastly, I realize that some would see it as prudent for me to volunteer to take over the UTLA Twitter handle, but that’s not my M.O. here. Frankly, someone is being paid to stay out of the classroom to help aid with communication and outreach for the union. I imagine they are overexerted and already working well beyond their limits. However, fax blasts are painfully slow when the vast majority of a constituent is Smartphone enabled. I’d imagine it is time to update how our union operates and communicates.