In Divergent the female protagonist, Tris faces her fears in a simulation as part of the final test to join the Dauntless faction. After facing fears of crows, drowning, and being burned alive, one of Tris’s final fears is best described as a fear of intimacy. More bluntly, Tris is shown as fearful of having sex with her character’s love interest, Tobias. In the drug-induced simulation, Tris must face her fear in order to find acceptance within the sect she is a part of:

He presses his mouth to mine, and my lips part. I thought it would be impossible to forget I was in a simulation. I was wrong; he makes everything else disintegrate.

His fingers find my jacket zipper and pull it down in one slow swipe until the zipper detaches. He tugs the jacket from my shoulders.

Oh, is all I can think as he kisses me again. Oh.

My fear is being with him. I have been wary of affection all my life, but I didn’t

know how deep that wariness went.

But this obstacle doesn’t feel the same as the others. It is a different kind of fear–nervous panic rather than blind terror.

He slides his hands down my arms and then squeezes my hips, his fingers sliding over the skin just above my belt, and I shiver.

I gently push him back and press my hands to my forehead. I have been attacked by crows and men with grotesque faces; I have been set on fire by the boy who almost threw me off a ledge; I have almost drowned–twice–and this is what I can’t cope with? This is the fear I have no solutions for–a boy I like, who wants to … have sex with me? (Roth, 2011, p. 393)

The passage challenges notions of what it means to be in control of one’s feelings and actions. The author tells readers that Tris “wants” to have sex with Tobias but the description is anything but enticing. The male character “presses his mouth,” and “tugs” clothing off, and “slides his hands” across the narrator’s body. For someone who is fearful she must give in to the invasive actions of her love interest. Where is the narrator’s agency here? More importantly, what does this passage suggest about femininity for readers? Is it to not be fearful when a boy one likes engages in similar activity? If this is her fear that she must overcome, should readers too find the willpower to endure such actions?

In similarly problematic depictions of female behavior, Taylor’s Daughter of Smoke and Bone takes an otherwise independent and strong-willed protagonist and renders her all but helpless when encountering an attractive, male foe. Early in Daughter of Smoke and Bone, Karou encounters an angel named, Akiva. For Karou, his beauty is exuded to the point of distraction. While Karou is fighting Akiva, her internal monologue depicts a woman flawed by her own sexuality; the fact that she finds this angel beautiful drives her actions in ways that are potentially life- threatening:

He stood a mere body’s length away, the point of his sword resting on the ground.

Oh, thought Karou, staring at him. Oh.

Angel indeed.

He stood revealed. The blade of his long sword gleamed white from the incandescence of his wings–vast shimmering wings, their reach so great they swept the walls on either side of the alley, each feather like the wind-tugged lick of a candle flame.

Those eyes.

His gaze was like a lit fuse, scorching the air between them. He was the most beautiful thing Karou had ever seen. Her first thought, incongruous but overpowering, was to memorize him so she could draw him later. (Taylor, 2011, p. 95)

Notice, across both Taylor and Roth’s depictions of sexual attraction as a weakness and fear in female protagonists the use of the italicized “Oh.” As if these women are stupefied and subsequently educated about sexuality through their encounters with men, both texts rely on this word as a means of suggesting the mental circuitry that wires women’s sexual awakenings. To her credit, Taylor crafts her description such that it does not focus on specific physical attributes. Instead, such depictions of beauty are largely left to the imagination of readers. What is problematic here is the constant loop of physical attraction that runs through Karou’s mind.

In addition to Karou’s overwhelming sexuality, Taylor’s text interweaves beauty and emotion for other characters in the text. For example, describing one of the ancillary characters, Taylor makes it clear that part of Liraz’s beauty is specifically related to her being female and “sharklike”. Taylor writes: “Though Hazael was more powerful, Liraz was more frightening, she always had been; perhaps she’d had to be, being female” (Taylor, 2011, p. 253). The construction of this sentence is striking: Taylor appears to deliberately draw connections that are powerful and problematic for young adult readers. It’s not simply that Liraz is frightening and female–this in itself would be worth considering in how it implicates beauty for readers. Instead, Liraz is frightening because “she’d had to be, being female.” Her frightening nature is due to how she is gendered by society. I want to make this use of “gender” as a verb clear: in the society of Daughter of Smoke and Bone Liraz is frightening and society casts her looks and frightfulness as particularly female attributes; they are cast, discursively, as what helps comprise her as a woman. For readers of this text the subtle construction of sentences like this one interweave feminine beauty – something that can be aspired to–as frightening. However, perhaps more importantly, this beauty and fearfulness can be seen as powerful: beautiful women have power and can enact changes in the world around them.

Immediately following the above sentence connecting femininity to frightfulness, Taylor writes, “Her [Liraz’s] pale hair was scraped back in severe plaits, and there was something coolly sharklike about her beauty: a flat, killer apathy” (Taylor, 2011, p. 253). This beauty is expanded to a less beautiful understanding of her appearance: her hair does not flow softly, it is “scraped” and “severe” and her appearance is “sharklike.” The harsh alliteration within this sentence cuts into the reading of the text and makes the description of this female angel something wholly inhuman, frightful and dangerous. Whereas Pudge’s view of Alaska [in Green’s Looking for Alaska] as an unknowable and vastly sexual woman placed control of female identity in the hands and gaze of the male character, Liraz here is a strong and beautiful woman. However, the description here makes her cold, calculating, and dangerous.

These are small microaggressions that female readers endure from one book to another. Instead of claiming that these readings of passages from Roth and Taylor critique too heavily minor, well-intentioned passages, I believe these are damning attributes of the literature we encourage young people to read non-critically. The messages of how females must look and behave that are read again and again in these texts typify identities that sexualize and pacify a female readership.

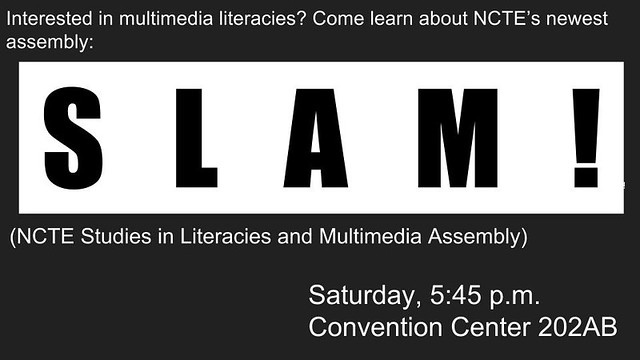

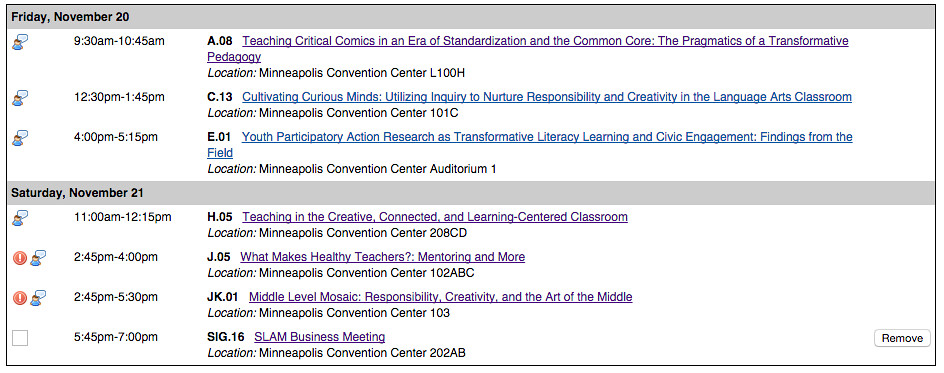

If you like comics, inquiry, YPAR, yoga, middle school, connected learning, or unkempt hairdos you should come say hello!

If you like comics, inquiry, YPAR, yoga, middle school, connected learning, or unkempt hairdos you should come say hello!