Pretty great trailer:

Pretty great trailer:

I guess the ranting tech-part of me felt obligated to point to this. I’m leaving it at that … for now. I am thinking through current acceptable use policies at school and their implications; this will be the final brick that will need to fall before pedagogy can be addressed.

And this is pretty much a solid read for any writer. A Visit From the Goon Squad is one of the best books I’ve read this year (the Pulitzer folks got this one right). The much-discussed “Powerpoint“ chapter is touching (and probably one of the few palatable uses of the clunky program). And this quote’s resonance on teaching implications is profound:

The desire to become a writer struck suddenly and without warning when she was a teenage backpacker in the early 1980s, traipsing across Europe, lonely and depressed, missing her family. This was the era of queuing for the public phone box: “There was a kind of intensity to the isolation of travel at that time that’s completely gone now. You had to wait in line at a phone place, and then there weren’t even answering machines. That feeling of waiting in line, paying for the phone and then not only having no one answer, but not being able to leave a message so that they would never know you called. It’s hard to fathom what that disconnection felt like. But I’m actually very grateful for it. Because it was extreme. And that kind of extreme isolation showed me that I wanted to be a writer.” [Hat tip to Ms. Hopper for pointing me toward both quote and profile.]

The human sense of isolation, loneliness, and disconnection as ascetic transformation is instantly recognizable and the kinds of feelings we strive (understandably) to avoid within formal learning spaces. However, apprenticeship/internship spaces to nurture, support and cultivate growth and occasional discomfort could be a useful area to think through educational reform.

I want to revisit a concept I began toying with in a post a few months back. In it, I reflected casually on the role of marketing and participatory media in the culmination of Kanye West’s release of My Dark Twisted Fantasy. I spoke broadly about the role that the mechanisms that musicians like Mr. West utilize to successfully launch an album’s release also have strong implications not only for what educators can do in a classroom, but–what I argue–they will have to do in order to maintain an equitable approach to teaching America’s youth.

In conferences, courses I am teaching, and occasionally on this blog, the statistic I’m regularly calling attention to (other than the continually frightening statistics related to the achievement gap) is the dwindling rate of college completion in the United States. It’s a large focus of the U.S. Department of Education’s Blueprint for Reform, and it meshes well with the books that have held me captive on a smattering of longish flights lately. And while policymakers and district officials continue to search for solutions to equip more students with the proficiencies needed to matriculate to and, eventually, graduate from four-year universities, I would posit that the skills to learn so are being represented by a sole College Dropout.

I hope to provide a handful of case studies (like Kanye) of the ways the tentacles of a Beautiful Dark Twisted Pedagogy are creeping into mainstream culture, influencing how we interact, think, and make choices about how we engage with the world around us. These examples are not emerging on the fringes of popular culture. On the contrary, they are the essence of what is revealing itself as a participatory youth culture. Kanye’s album was a critical and commercial success. These are examples that are, for now, largely lacking in the kinds of instructional practices most teachers are utilizing in their classrooms. They are not themselves critical. On the contrary, they are capitalistic by nature and are seen in the marketing ploys of musicians, film companies, and general products.

Too often, we look at the realm of capitalism and disregard it wholesale; naw, that [person, product, event] ain’t down. And yet, while the content is a problematic perpetuation of marketing practices, the approaches themselves speak to the ways students are engaging, interacting, and approaching informal learning.

Approaching the challenging domain of capitalism with a lens of pragmatic optimism, I’m trying, here, to direct our attention toward the potential of participatory media as enacted by for-profit companies and think through ways these can be harnessed for wholesale social transformation.

All that being said, today, I want to talk about Wheat Thins.

Are you following Wheat Thins on Twitter? (Assuming you’re even on Twitter*)…

With commercials that appear extremely low-fi, Wheat Thins crafted a marketing campaign that not only went viral, but encouraged participation and amplification of their brand. They did this by highlighting real individuals and real tweets:

And yes, Chris Macho is real (there’s a commercial where the Wheat Thins reps prove they are uber real). And yes, as a result of his awesomeness, he’s gotten a TON of people to follow him on Twitter:

Not only did thousands of people follow Wheat Thins, but the company got people to willingly engage in dialogue, share what they liked about the company and, essentially, advertise why Wheat Thins are an awesome snack, accessory, and guitar pick.

Wheat Thins essentially nudged a huge market to become mavens, salesmen, and connectors (to lift Gladwell’s labels**through Twitter; the incentive may be a sweepstakes-like gimmick (send a note about wheat thins, and you might end up on a commercial), but I can also reasonably imagine that the participants had fun feeling engaged in the marketing strategy. And considering that this campaign has been going on for months, it’s telling that people are still tweeting in hopes of their tweet being “heard” today:

Again, this isn’t a post pointing to a secret phenomenon – the ads are seen by millions, tweeted by thousands, and you’ve likely seen them before. They aren’t doing anything new either: companies respond to tweets, follow/like other information on social networks all the time, and produce DIY-style video for their products on a regular basis. In essence, companies mimic what young people regularly do on their own; they do what kids do when they are having fun hanging out, messing around, and geeking out.

As educators, how can we inform our pedagogy by Wheat Thins? Perhaps not the most astutely worded of education-related questions, but a necessary one nonetheless. The company has made participating in their ad campaign fun, silly, and sticky. Why can’t our classrooms leverage similar tools to get young people excited, in conversation, and networking globally around classroom content? I am not speaking about co-opting youth practices within a classroom. On the contrary, I am speaking about a large-scale effort to update the classroom into the kinds of networked ecologies that are utilized for interaction everywhere except for in schools.

A Beautiful Dark Twisted Pedagogy is one that envelops students in opportunities to engage with extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. It allows youth to speak back to the content and see work in dialogue. It begins with youth interest and quickly amplifies key concepts that resonate within a classroom and well beyond. And while I can’t pinpoint a specific series of steps that can be taken to “update” one classroom after another, listening to young people, delving into previews for blockbusters, forcing yourself to spend sometime noticing commercial during primetime television (even if you hate American Idol and have sworn off MTV), are going to be the best signals for how young people’s attention is being drawn both outside of schools and–if you’re at all having the kinds of phone-use woes I’m hearing from many of my colleagues–in your classrooms.

A gimmick like Wheat Thins’ isn’t going to save our schools. It is, however, going to point towards ways we can work hand-in-hand with our students and communities to save our schools.

—

*Twitter footnote: I was so proud of this tweet that I had to share it:

** Sorry, after teaching The Tipping Point a half dozen times to seniors, this is what happens.

Someone actually read (and provided notes for) “Patterns Towards Da Future,” a paper I co-wrote.

A couple weeks ago, I got an email from a fellow teacher, Jason Sellers. We’d met several months ago while I was in Orlando for NCTE and he for the National Writing Project’s annual conference. Jason is a high school English teacher in Staunton, IL, a rural high school 45 minutes outside of St. Louis. He’s also a NWP Technology Liaison with the Piasa Bluffs Writing Project, a member of the Cultural Landscapes Collaboratory (an organization that provides professional development to schools), a Hill Country blues guitarist, a motorcycle adventurer, and an MMA fighter.

Discussing the ways we get tied up with information, we thought it would be useful to share out some ways we are organizing, synthesizing, and being able to just remember the myriad information strands we are engaging with on a day-to-day basis. Below we begin our discussion of academic productivity.

How do you manage the information you read in books for future reference?

Jason:

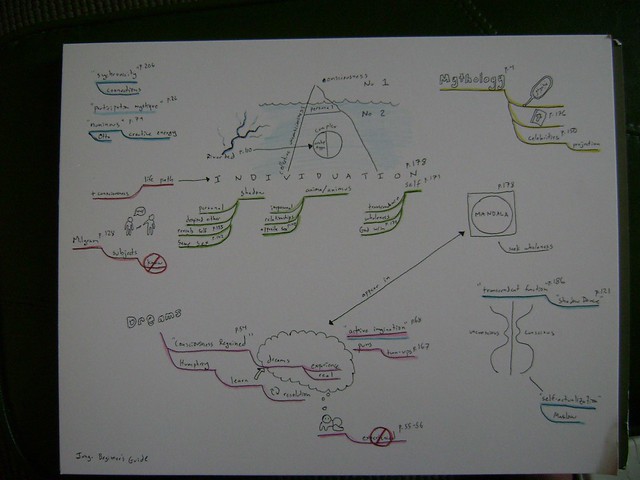

Here are possible options I’ve explored: purchasing traditional books and writing in the margins; purchasing e-books and using Kindle’s highlight feature to save passages; taking snapshots of passages with my cell phone and saving them in EverNote; taking notes in a journal; creating mindmaps.

My main reason for leaning towards ebooks and/or saving passages in Evernote is that I feel books will inevitably move to an electronic format. I don’t want to have to comb through my collection of paper books for marginalia, which I’ll then have to convert to digital format.

The problem with margin writing and ebooks is that they both require purchasing the book. I can’t write in books from the library, and pirated e-books are difficult to find online (waiting on the book equivalent of Napster). Ultimitely, I ruled these two options out, because I’m poor.

I prefer to check books out from the library. I tried taking snapshots of passages of library books with my cell phone. This may be a good method, but I have an older model of cell phone with a crappy camera — doesn’t capture text very well. Someone with an iPhone might be more successful doing this.

The best method I’ve found for retaining information in books is to mindmap the book. I’ve been using this method that past two months after reading Tony Buzan’s The Mind Map Book. I keep a 8.5″ x 11″ sketchbook with me while I read, and make notes with page numbers for quick reference. That way, I have all the information on one page. Single words and short phrases are enough for me to remember whatever it is I need to remember, and page #s help me track down the passage if I need to cite it directly.

When I finish a mind map, I take a photo, upload it to EverNote, and tag it. Easy to find, and EverNote recognizes handwriting, so it’s searachable.

Thanks again for starting off this discussion Jason. I’m definitely interested in finding out more about other people’s research and creative practices (and hope a few of you will share in the comments below).

As for me, if I’m reading generally, I do a lot of annotating in most books (with exceptions noted below). I also compile a note-taking sheet at the back of most books that allows me to reference back to specific topics and pages I think will come in handy later on.

If I’m reading for a specific project, I’ll also probably start typing my notes or direct quotations as they become prevalent. As I’ve talked about before, Scrivener is an essential note-taking tool for me and for how I organize work related stuff. If there are quotes, passages, or main ideas I want to draw upon or puzzle through, I will type those directly into Scrivener for later–they may get discarded, they may get expanded, they may lead to another book and to another ad naseum, but the point is to get them to the general “space” to which they are related.

I have a pretty strict but impractical approach to writing in books that I’ve been stuck with since beginning my undergraduate work. Basically, any literary, YA, or leisure reading text gets a kind of no-writing embargo placed on it. I’ll admit that the materialistic part of me appreciates the book as a product, especially Books So Ridiculously Awesome You Don’t Even Know What To Do With Them (BSRAYDEKWTDWT). I’ve amassed a handful of first editions of books that have felt important to me at one point in my life or another, and I’ll buy more than one edition of a book to have a “reader’s copy” of a book I don’t feel comfortable risking getting tattered by borrowers of books. Geek Love, Infinite Jest (though the second printing with Vollmann’s name correctly spelled, unfortunately), and–come to mention it–a healthy portion of Bill’s books as well:

Now, when it comes to academic texts, many get put through the wringer, as do books that are often drawn upon or which it’s a good idea to keep in a back pocket once in a while – some of Salinger’s books fit in this category and I’ve probably bought or given away a copy of Franny and Zooey on an annual basis.

The tricky thing for me is when a book straddles the line between work and play (Dewey reminds us that this is a false divide in the first place). So, having to read House of Leaves for an undergraduate seminar, made me struggle between writing in and not annotating (this sometimes leads me to do things like buy two copies of a book … I am not proud of this).

As for non-fiction, every page and inch of the book is fair game in terms of annotation. Some of my critical theory books are difficult to read due to third and fourth rounds of annotations. In general, however, the very last page of the book becomes a pseudo-index for me of pages, phrases, and ideas I may want to reference at some time in the future. The page is usually very sloppy may have notes to random people, doodling, and references to things that may not make sense to me. It’s pretty common for me to be unable to decipher some of these notes later on – the fact that many of these books are at least partly read in cars and on airplanes makes the notes that much messier. Here’s the back page of this book that I read last week:

Again, very random notes and jottings. However, considering that the majority of my academic books have similar pages, my library very quickly is distilled to a handful of pages that I can cull together around specific projects. It leaves me in the midst of an unfinished conversation I can pick up and add to very quickly.

So that’s a snapshot of two approaches to digesting reading materials. What are your approaches? I think we’ll, eventually, work through our approaches to writing, organizing, and moving from others’ work to our own. This reflective practice reminded me of this and I hope this can be a way to think about the different approaches pedagogues and researchers take in engaging with the mental labor of educating America.

Flying to Boston for the Urban Sites Network Conference, I read Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Really insightful report. Though I’ll go over a few main ideas from the text below, it’s worth a look.

Some main takeaways:

The implications of the study captured in the book are significant. However, in considering the need for a college degree in gaining entry into the competitive workforce, the study portrays a significant gateway American youth must pass through.

The study highlights the “college for all” mentality that is perceived throughout the country. At the same time it shows that not only are students less prepared for the rigors of college, they also expect to be able to achieve competitively despite a lack of academic focus in their secondary education. And, ultimately, these students (though there is a significant rate of students dropping out of college) complete degrees by navigating through easier courses; the statistics on the amount of students that never write compositions longer than 20 pages by the time they graduate is both significant and unsurprising in the context of the disembodied learning experiences that students are currently undergoing.

What’s not said, in the book, however, is just how necessary college is. Students are expecting to go through college–even when they are not motivated in high school–because, if they want a middle-class level job, they need a bachelor’s degree (at a minimum). Essentially, we are forcing students to go through a program they are not prepared for and may not be interested in, in order to get a job afterwards. On the other side of this are the thousands of students not represented in the study: the students that don’t even bother with college in the first place. In a school like Manual Arts, a school of black and Latino students, this is roughly 90% of our students … more than 3,000 of them. They aren’t playing the college game, they are not taming college professors, they are not not visiting professors during office hours, they are not spending too much time socializing in fraternities and sororities, and they are not worried about the debt that so often comes with entering the sphere of higher education.

I get that that is not the purpose of the book. Frankly, I found Academically Adrift compelling–the hard data that fills roughly a third of the book as an appendix is a valuable resource that will eventually guide a Socratic conversation with my high school students. I bring up the unspoken story of the students who aren’t entering the drift-free world of college because it brings up the further segmentation of American society. By the time students get to college, the achievement gap cleaves working class students well away from their counterparts and leaves them with few options (aside from the marginal small percentage of students that “make it” and perpetuate the cycle of inequality). By the time students finish college, they are further partitioned by race and class: many will not finish, a majority will finish with a bare minimum of engagement and negligible amounts of learning (less selective universities have looser general education requirements–students will usually take easier classes at these schools), and a small fraction of students will leave college with the kinds of higher order critical thinking skills that universities were established to instill. Our achievement gap essentially becomes a series of canyons of exacerbated inequality.

Wondering if getting death threats and calling a new hip-hop album “I”m Gay” elevate the discourse.

Wondering when these actions will funnel into youth popular culture at my school.

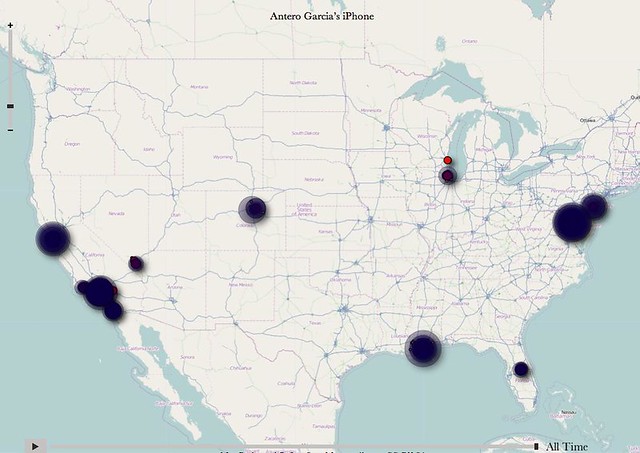

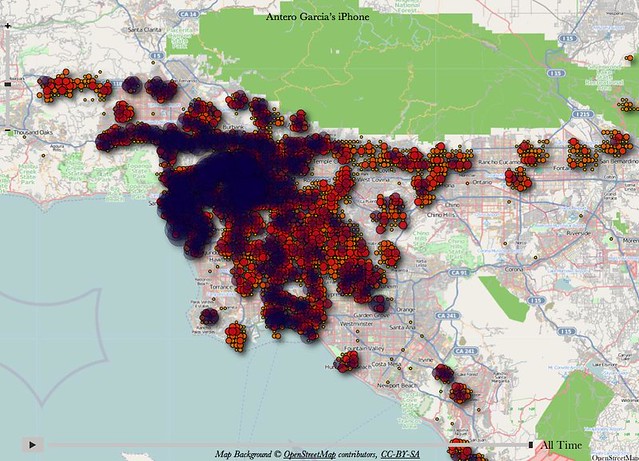

So I guess the above map is about right. The location tracking for my phone only started when I switched to the iPhone 4, so the map above is indicative for a little less than a year at this point. Hey, check it out, you can see where I live:

Oh, if you haven’t heard, it was recently discovered that iPhone systems have been tracking where the phones have been and keeping a log on your computer. You can read more about this and see a visualization of your phone’s movement over here. [And since the map can be read down to street level, it is relatively easy to simply find the most frequently visited locations to deduce one’s residence, work place, hangouts, etc.]

If anything, the information here poses a couple of significant opportunities for us as educators. Several of my social studies colleagues were recently awarded a UCLA Teaching Initiated Inquiry Project grant to focus on GIS-related skills. How great could this kind of track data be to look at the movement patterns of youth in and around the city?

I can’t say I’m all that surprised that a log of where my phone has been is being maintained. Frankly, I wouldn’t even be surprised if I were to later find out that the information is being sent elsewhere – it would not be that different from targeted advertising in my Gmail or Facebook accounts. What’s important to realize here is that, once again, the notion of what we teach in terms of critical literacy is expanding. Not only do we need to teach students how to use new media tools but also to question and understand the implications of their use. The wording difference may be slight, but this is a significant change in what literacy development means.

In a sense, we are looking at a symbiotic relationship between a tool and its wielder; we rely on mobile media devices throughout the day for various functions and it too tracks and maintains a log of where and what we are doing.

Of course, the real problem is that this data becomes tied to individuals. Pinpointing migrant patterns of undocumented students, for instance, would be a serious concern. Likewise, after school locations of gang-affiliated students, congregation areas for truancy or just about any kind of published data about where someone is if they don’t wish that information to be known is a real concern. Put even more clearly, the FAQ on the iPhone Tracker site states:

The most immediate problem is that this data is stored in an easily-readable form on your machine. Any other program you run or user with access to your machine can look through it.

The more fundamental problem is that Apple are collecting this information at all. Cell-phone providers collect similar data almost inevitably as part of their operations, but it’s kept behind their firewall. It normally requires a court order to gain access to it, whereas this is available to anyone who can get their hands on your phone or computer.

By passively logging your location without your permission, Apple have made it possible for anyone from a jealous spouse to a private investigator to get a detailed picture of your movements.

Literacy development today includes understanding the rights we sacrifice in stepping into the realm of participatory media. Cognizance of how search is being manipulated, of how we are being marketed to on Facebook, and of how your movements are being tracked are all new skills that need to be developed within students today. If we are serious about thinking beyond the work of New London, I am arguing here that literacy development is going to be about the underlying symmetry of use and cognizance when interacting with cloud-connected tools.

I’ve started blogging for DML Central. My first post went up yesterday and you can read it here.

If anything, the material I write for the DML Central blog will extend ideas I’ve been fulminating over here over the past couple of years (if you are at all an occasional peruser of The American Crawl, you won’t be too surprised by the concepts I write over there).

My first post really focuses on the need for DML related pedagogy and innovation to occur within classrooms and formal learning environments. As I think more about this, I would argue that what DML faces is a charter selection problem.

I’ll expand on this in the coming weeks, here, and hope to use this space to act as a scratchboard for ideas for future posts. (I’ll only be blogging monthly or so over at DML, so if you have suggestions for things you’d like voiced or represented, please drop me a line.

I’m honored to have an article I wrote a couple of years ago, “Rethinking MySpace,” republished in the newest book by the Rethinking Schools group, Rethinking Popular Culture and Media.

In terms of publications related to teaching practice, Rethinking Schools is basically the only periodical I consistently read, and I want to encourage any teacher to read and support this work. Rethinking Schools is put together by full time teachers who do this out of a commitment to social justice teaching; as much as I am proud to count myself as a contributor to the magazine, I can say with utmost confidence that I’d still be reading, subscribing, and recommending Rethinking Schools’ materials regardless of if I had written for them.

Now, I realize it is 2011 and I’m now in the position of promoting an article about MySpace. Like Friendster, MySpace has pretty much come and gone. [A good read related to the downfall of MySpace can be found here.]

Talking with students recently, several admitted that they still have an account there, but that for the most part they are almost entirely interacting with peers on Facebook. [This is significantly recent shift that I want to explore further in future posts. Less than a year ago, I would talk to students about Facebook and it was still not considered “cool” or accepted by youth. This was pretty much still the norm.]

In any case, regardless of which corporate entity students are adopting for their social networking, participatory media has directly changed the way students communicate, socialize, learn. The practices I describe in “Rethinking MySpace” are far from obsolete and the challenges we educators face are becoming more complex.

Critically, we need to recognize that many people (not just students) are engaging with new media tools without questioning the structures that are in place: How are companies making money off of my decisions in a space like Facebook? How is this money being used? What capitalist ideologies do I reify each time I “like” a friend’s status update, retweet, or respond to a colleague’s request on a network like academia.edu?

The literacy skills we instill in students need to include not only how to interact with the new tools that have emerged over the past few years, but also a recognition to understand the implications of using these tools.

In upcoming posts, I want to expand on ideas I began with in “Rethinking MySpace,” question how social networking practices have transformed my practice, and explore what is happening in larger conversations about privacy and social networking. In the meantime, please support Rethinking Schools (and their sister site Not Waiting For Superman).